Stories of Michigan Medicine on the Front Lines

Authors |

"Walking into the hospital main entrance this AM, I saw a special thing. A family was waiting for their loved one outside the hospital. Flowers and banners were in hand. One read, 'Congrats on beating #COVID' and another 'Welcome Home Dad.' The joy and love was palpable."

Vineet Chopra, M.D., associate professor of internal medicine and chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine, tweeted these words on April 21. The number of COVID-19 patients at Michigan Medicine had peaked, the curve had flattened, and a slow downward trend had begun.

Chopra's knack for finding the bright spots in dark times also emerged two weeks earlier, in the form of a tweet that inspired followers near and far: I walked a patient out of the hospital today. They were being discharged after 17 days in the hospital with #COVID19. When I met them, we were talking about #ecmo. Today — we were talking about friends and family. That's the story, people. That's the story.

Yet he knows better than anyone that the full story of COVID-19 at Michigan Medicine was marked by highs and lows, painful deaths and surprising recoveries. Chopra was one of the faculty and staff members who were on the front line of the health system's response to the pandemic. He treated patients when providers were still learning what symptoms people who had COVID-19 presented with. He saw patients young and old, and those who were fellow physicians, nurses, and other health care workers.

While the entire world was trying to catch its breath, providers at Michigan Medicine treated patients who needed to be transferred from overflowing Detroit hospitals. They prepared an infectious containment unit within days. Providers and other employees worked with people from all parts of the hospital, with all the usual divides knocked down for the sake of expediency and finding the best way to treat people, right here, right now, and without a moment to spare.

Here, we tell some of their stories.

"WHY DID ONE DO OK AND NOT THE OTHER?"

In late April, Valerie Vaughn, M.D., treated two patients who had COVID-19. Having arrived at the hospital at roughly the same time, they were in the same room on the seventh floor. Neither of them needed to be in the ICU, but they still had major oxygen needs. Vaughn had helped create a new type of moderate-care room, where patients like this could make use of heated high-flow oxygen devices without having to be in the ICU.

When it was time to examine the patients, Vaughn suited up: n95 face mask, face shield, gown, and gloves. Vaughn made a habit of passing out her business card while caring for COVID-19 patients, so they would know what she looks like behind all the gear. "By the time you walk in, you're already sweating," she says. These two patients had been faring equally all week, neither improving nor deteriorating. Until this day, every time one of these patients stood, their oxygen would dip, so they were both confined to their beds.

On this day, however, her first patient was finally well enough to be taken off of the heated high-flow oxygen. When she entered the room, he stood and walked around, joking and showing off his new mobility by doing squats. Vaughn realized in that moment that he would go home. She was flooded with "absolute joy."

Then Vaughn visited his neighbor, a man who had lost his wife a year ago and had had long conversations with health care workers throughout the week about his end-of-life choices. She knew he did not want to be kept alive on machines. But his fate had changed in the opposite direction of his roommate. His oxygen needs were higher, and it was time to intubate him and put him on a ventilator, or acknowledge that this was the end.

The team called his daughter. "It's one of the toughest phone calls to make." Vaughn felt like she knew this woman after their phone calls over the course of the week, but they had never met in person. "We don't get to meet the families anymore." The only exception was for end-of-life visits.

"She got a chance to come in and say goodbye to her dad. She took his wedding ring and his cell phone. … I got to watch as his neighbor was wheeled out of the hospital to the loving arms of his wife.

"Why did the one do OK and not the other one? … It's just so random how coronavirus affects people."

THE TIRELESS WORK OF INFECTION PREVENTION

At 7:30 a.m. on a day at the height of the COVID-19 surge, Amanda Valyko, MPH, director of Infection Prevention and Epidemiology (IPE), arrived in the command center at University Hospital. Before the pandemic, "I would have probably been trying to convince my kids to put their shoes on to get out the door." But schools and daycares were closed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, and "the IPE team is all-hands-on-deck for COVID-19."

Valyko's day actually began at midnight, when she checked her 5-year-old son's blood sugar and gave him a bolus of insulin. At a 3 a.m. check-in, he was stable. She checked a baby monitor and was relieved to find her almost-2-year-old still sleeping. At 5:30 a.m., Valyko's alarm went off again. Exhausted, she hit the snooze button. When she got up, she did a quick check of emails to see if she missed anything overnight.

At the command center, Valyko had four meetings before 10:30 a.m., one on the topic that occupied a lot of time at the beginning of the surge: fit testing for n95 masks. Most of Valyko's meetings were virtual throughout the pandemic, but she did spend a couple of hours that day working in another building with other IPE team members who were looking into possible employee exposure to patients who may have had COVID-19 and fielding related questions. She also reviewed updates related to COVID-19 and did research to inform infection prevention recommendations for hospital leaders. A few meetings and "many, many emails" later, she was on her way home.

One silver lining: her commute, which had been up to an hour long in pre-pandemic traffic, was half as long on the near-empty roads.

FEAR AT THE THRESHOLD OF A COVID-19 PATIENT ROOM

"I'm going to tell you honestly. I was frightened to death," says David Pinsky, M.D., division chief of cardiovascular medicine. He had volunteered to care for COVID-19 patients, and he was about to enter the room of an infected person for the first time. He was obsessed with the checklist for safe donning and doffing of personal protective equipment (PPE). "I went through it a hundred times in my head. I washed my hands. I put on the gown. I washed my hands. I put on the gloves. I washed my hands. I put on a mask. I wiped the goggles down. I put the goggles on." His family frequently asked him to be sure he was properly protected. "I even asked one of my colleagues to snap a photo so I could send to my wife, kids, mother, sister — all in health care and all at risk — so they could be sure I did it right." Then he closed his eyes and asked himself, "Am I good to go?"

His fear fell away when he entered the room. "It felt right," he says. "The patients needed us."

During one week in April, Pinsky was caring for two COVID-19 patients who were in the high-risk category because they had cardiovascular disease. One patient, who had previously had a heart transplant, improved and was able to go home. The other, however, didn't make it. "He was coherent at one point, and I was able to get his daughter on the phone." It was probably the last time the patient would talk to a family member. "There's nothing worse than dying alone," says Pinsky. "It's very important for us to be there. We were often the family that wasn't family."

There were times in the patient rooms when the mundane threatened to become serious. "Often in pulling the stethoscope out of my ears, or doffing my mask when I was out of the room, my glasses would sometimes get entangled," says Pinsky. "I had to pause, and carefully unwind the earpieces ... then regroup."

Despite Pinsky's fear upon entering the room, leaving the room was actually just as risky. He notes that during the Ebola crisis, improperly doffing PPE led to a lot of infection. After going through the doffing process, Pinsky went home and "showered and showered."

"Then you wait. You stay away for a week to 14 days, waiting to see if something kicks you in the guts," he says. "I'm fortunate that nothing did."

THE CLINICIAN/ RESEARCHER: A COVID-FIGHTING DOUBLE THREAT

Mahshid Abir, M.D. (M.Sc. 2011), was leaving her house one day in mid-April when her 10-year-old son heard the garage door rising. He yelled to her from a second-floor window: "Mom, don't get COVID!"

His concern was genuine; Abir is an associate professor of emergency medicine, and she had direct contact with COVID-19 patients during most of her shifts for the month leading up to that day. "Every time when I come home, I go right from the garage to the laundry room, then straight to shower. I don't hug my kids; I don't kiss my husband," she says.

Abir was relieved that Ann Arbor was not hit initially with the same patient volume as Detroit or New York. Even so, she says, the pandemic will have a profound impact on how Michigan Medicine operates. She is sure of that because of her experience as a clinician, as well as her role as a researcher who studies health services through a joint appointment at U-M and the RAND Corporation. For 10 years, she has studied hospital preparedness — a topic that is always important, but never more so than during the first wave of COVID-19.

"Think of the social unrest and political change around the world. The geopolitical climate is changing," she says. "This is not going to be the last pandemic. This is not going to be the last disaster. We, as researchers, need to be nimble. We don't have months; we don't have years."

Abir has been impressed with Michigan Medicine and U-M's responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the rapid switch to video appointments for many patients, the creation of a PPE disinfection process that uses a UV-light-based treatment, and the rapid establishment of special units just for COVID-19 patients. "The pandemic is forcing innovation out of desperation," she says.

A more profound silver lining of the pandemic, she says, could be a change in the way people within and outside of health care reconsider all processes, actions, and behaviors.

"Do we want to go back to normal, or do we want to reevaluate some of those societal rituals? At least based on conversations with family, friends, and colleagues, people are spending more time with family. They are spending more time reading. They are thinking more, and reflecting more," she says. "I wish we would do more of that. In a world of social media and people not talking much to each other anymore, perhaps this is an opportunity to hit that reset button. Perhaps we can leverage the situation to create positive change."

"WITH EVERY PATIENT, WE'RE CONCERNED"

Sarah Erickson, RN, was living in a hotel. Each morning, she got up at 5:30 and sat on the couch in her room with a cup of coffee, centering herself for the day. When she left for work on April 14, someone in the lobby reminded her to be safe — the pandemic version of "Have a good day." Erickson's commute was short, and she saw only a couple of other cars on the roads.

An ER nurse at University Hospital, Erickson jumped at the chance to move into "high-risk housing" when Michigan Medicine made the offer to employees on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. Erickson's family moved to Michigan a couple of years ago so that her son, who has congenital heart disease, could be treated at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Erickson has been worried he might contract COVID-19. "That first shift at the hospital after moving [into the hotel], it felt like a weight had been lifted," she says. "[My son] has survived cardiac arrest … he's going to survive his mother being an ER nurse."

At the hospital, Erickson headed for the break room to begin the shift-change process, which she said had been taking longer and longer due to COVID-19 protocols and updates. "They've moved us into what used to be a visitor center, since we don't have visitors anymore." The larger space allowed for more social distancing and room for the big wire carts of personal protective equipment lining two of the walls.

"The ER is normally so loud you can't hear yourself think. Organized chaos," Erickson says. But the early weeks of the surge had been strangely quiet. "All the patient doors are closed. Voices are hushed."

Her first patient of the day came in without COVID-19 symptoms. "But with every patient, we're concerned," she says. "Because you don't know; they've been out in public." The patient was mentally ill and unable to give a coherent account of where she'd been and what she'd been doing. "When you can't get an accurate history, you don't know. Are we at risk? Are we not at risk?"

At other times, the risk was more obvious. When a patient came in with shortness of breath and a dry cough, Erickson wore full protection. Sometimes a seemingly benign situation "all of a sudden becomes a COVID workup." That's when anxiety creeps in. "You find yourself thinking, 'What was I wearing? Did I do the right hygiene? Donning and doffing — did I do it right?'"

The COVID workups were particularly challenging. "You have to have two people: a clean person and a dirty person," says Erickson. "It's a lot to orchestrate." When the patient goes to a different part of the hospital to have a test, that testing room gets shut down afterward for extensive cleaning.

Breaks were also more complicated than they had been before. Only four people were allowed in the room at a time, and "they put Xes outside the breakroom, so we know how far apart to stand," says Erickson, who was grateful for the food that community members and restaurants donated to front-line workers. They also received tea, socks, T-shirts, and "headbands with buttons on them so we can wear our masks without hurting our ears," she says. "I feel, for the first time in my career, people are starting to realize what nurses do."

Back at the Residence Inn by Marriott, Erickson waited her turn to take the elevator up to her room. The only other people she saw were health care professionals. "The front desk told me that before Michigan Medicine was providing staff with rooms, they only had a 13% occupancy; now they have 49%." Back in her room, she set her shoes in a designated spot. "I take everything off right inside the door. I put all my scrubs in a garbage bag, and I go straight to the shower." After scrubbing off any possible coronavirus, Erickson talked with her husband and three kids on FaceTime. On days when she wasn't at the hospital, she'd spend the day in her room, mentally preparing for the next shift of COVID-19 patients.

"THIS COULD BE US"

Vineet Chopra, M.D., associate professor of internal medicine and chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine, served as medical director for the Regional Infectious Containment Unit (RICU) as it opened, along with co-directors Valerie Vaughn, M.D., and Chris Smith, M.D. In March, one of the first patients in the unit was a physician who had trained at U-M and contracted COVID-19 while working at the Detroit Medical Center.

"He was transferred to us for ECMO," Chopra said, noting that Michigan Medicine has the highest number of ECMO machines in the state. "The anesthesiologist caring for him was his classmate. We all had the sense that, 'this could be us.'"

Disconnected from the outside world, the patient's spirits were brightened one day when his daughter sang "You Are my Sunshine" to him over the phone. Weeks later, the physician had recovered and was discharged.

Many of the patients in the RICU didn't survive the grueling disease. Some had preexisting health conditions, while others were healthy before contracting the virus. "This disease spares no one," Chopra said. "In these last moments, we are the patients' family. I've personally held hands with several of them when they were in the unit."

Chopra was an intern in New York City during 9/11. He worked on H1N1 flu cases. He volunteered to treat Ebola patients. "COVID is unlike any of those," he said. "Just the sheer number. The resources these patients need. I don't think any of us fully appreciated the complexity of caring for COVID patients in the beginning."

In spite of that complexity — or perhaps because of it — Michigan Medicine was able to shift into high gear quickly, Chopra said, with all relevant specialties coming together and "operating with agility."

On a day in mid-April, Chopra was leaving the hospital around 6 p.m. when he saw a man in his late-50s leaving with his family. He recognized the patient as someone he'd treated in the RICU. "I quickened my step and talked to him. I had the incredible privilege of walking him out of the hospital," Chopra recalled. "He said, 'I'm going to go home and have a big steak.'

"Then he turned around and said, 'Thank you for saving my life.'"

WHEN SOMEONE CAN'T BREATHE

The work Kate Cheng, R.T., did during the surge of COVID-19 patients at University Hospital was no different than the work she had been doing before the pandemic. But the pace was much faster, and the stakes were much higher.

Cheng is a respiratory therapist, so her services have been in high demand since mid-March. On one busy day, Cheng estimates she donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE) about 30 times to enter COVID-19 patient rooms. "Some places don't even have what we have, so we were pretty happy [to have enough PPE]," Cheng says.

When someone can't breathe, it's usually considered an emergency. But there are no emergencies in a pandemic. Brian Woodcock, M.D., assistant professor of anesthesiology, reiterated that popular adage, and Cheng says it was the best advice she received. "It gave me permission to stop a minute and take care of myself," she says. "If I walk into a patient's room and I'm infected, I'm not doing anybody any good."

Cheng needed to enter patient rooms to adjust ventilator settings, suction out their breathing tubes, and help with proning, the practice of turning a patient onto their stomach to improve breathing.

Proning is a routine procedure for patients on a ventilator. It can take about a half dozen health care workers to turn a COVID-19 patient over safely. "Ideally you have three people on one side of the bed, three on the other, and a respiratory therapist at the head of the bed to watch the breathing tube," says Cheng. "We have a bottom sheet, and we put a top sheet over them and make them into a burrito." This allows the nurses and technicians to flip the patient somewhat gracefully.

In a negative pressure room, where staff are using walkie-talkies and writing on windows to communicate with colleagues in an attempt to limit the number of people who need to enter the room, six is a crowd. At the head of the bed, Cheng's main focus is ensuring the patient doesn't get disconnected from the ventilator — which is almost as important to her colleagues' health as it is to the patient's. "If it pops off, I'm exposing everybody to COVID."

Transfers are also critical moments requiring Cheng's expertise. If a patient on a ventilator needed to move from a moderate-care unit to the ICU, Cheng would follow along to monitor the breathing equipment. "I've worked at the U-M for 22 years, and I've gone on more transports in the last two months than in 22 years," she said in May. Cheng's FitBit clocked in at 22,000 steps one day at the height of the surge, more than twice her usual count.

The downward trend in COVID-19 patient numbers at Michigan Medicine after mid-April allowed Cheng to catch her breath. "This last week was the first that we were feeling like we were back to normal," Cheng said in late May. "It was the first day I pet my dog when I got back home before taking a shower."

"THERE'S A GOOD CHANCE YOU WON'T SURVIVE THIS"

Before Brinton Robison, P.A., volunteered to help on the front lines of the pandemic, he was a physician assistant in neurological oncology at the Rogel Cancer Center. He had plenty of experience with difficult conversations, a skill he used frequently during the surge to talk to the family members of COVID-19 patients. "Patients' families are extremely grateful," says Robison, referring to the daily calls he made to update family members. "That's one of the most rewarding things about my time on the COVID units."

One morning at 7:30 a.m., he received a page about a COVID-19 patient who was admitted the day before and who had been faring well. "About five minutes later, I get [another] page saying, 'You should come see this patient. He isn't doing very well,'" says Robison. About three minutes later, the page said, "Come right now." Robison immediately observed that the patient's "breathing was awful" and helped the nurse set in motion the process to get the patient moved to the ICU. He examined the patient and told him he would be moving. Then Robison began the process of informing everyone involved: the supervising physician who would call the ICU team, the nurses who needed to know about this patient's extra medications, and the respiratory therapists who would help the patient breathe better in the ICU. It was a hectic half hour from the time Robison got paged to when the patient was en route to more intensive care.

Despite the stress, Robison didn't forget that there was one more person he needed to inform: the patient's wife. Though he usually began calling patients' family members at 3 p.m., he made an exception in this instance. He didn't want the patient's wife to be surprised by a call from the ICU before he had a chance to tell her that her husband's condition had deteriorated. He also wanted to reassure her that they were doing everything they could for her husband.

Sometimes, the conversations he had with patients and their family members were more difficult. On a particularly hard day, Robison recalls telling a patient, "There's a good chance you won't survive this." Earlier in his stay, the patient — the same one Vaughn treated, as described above — had made it clear he didn't want to be put on a ventilator. Robison confirmed that this was still the patient's wish and called the man's daughter to tell her the news. Then Robison facilitated a visit from his daughter.

Robison usually tried to leave his work at the hospital, but "that one was a little hard not to take home," he says. "That was a heavy day. You have these conversations with family, and things just change so quickly. … He was totally fine the day before. … It's a humbling experience."

Robison was off work the next few days, but he continued to check on the patient's status. "He lasted a little longer than we thought he would. Within a few days, he had passed away from COVID."

"WE'RE ALL ON THE SAME TEAM"

On the 10th floor of C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, guest services specialist Alex Higginbotham keeps watch. When Higginbotham's shift began at 6 p.m. on April 14, the outgoing guest services specialist made him aware of one issue: a possible exception to the pandemic policy of having only one assigned parent per patient. "The patient I was told about was possibly in decline during the daytime," he said, and the father wanted permission to be with the mother and the patient. When the father arrived, Higginbotham would need to contact nursing leadership to make sure the father had permission to enter.

Throughout the pandemic, Guest Services staff members played an important role, as did Security, Entrance Services, and numerous other units. In addition to screening people at hospital entrances, they were charged with guarding personal protective equipment and other valuable resources from theft. They also helped facilitate safe transport of patients who had possible and confirmed COVID-19 diagnoses.

One of the keys to creating safety and a sense of security is developing relationships, a large component of Higginbotham's job. Working in a pediatric unit, he helped family members navigate the difficulty of the COVID-19 one-parent visitation policy. "This is a really challenging floor to work on, and it can be heartbreaking at times. I hold on to the good moments when I hear good news from the parents. … I also am there to help them through challenging times." If there were visitors in the family lounge past regular hours, Higginbotham talked with nurses to get a better picture of what was going on. "In most cases it really depends on the situation if they are allowed to [stay].

"Anything to reduce confusion and frustration is very important," says Higginbotham. "We're all on the same team."

UNBREAKABLE BONDS AND FRONT-LINE FACIALS

Preet Shokar, RN, had not worked at Michigan Medicine before the pandemic. A registered nurse working for multiple Michigan health care systems, Shokar responded to a call for volunteers and ended up working with some of the sickest COVID-19 patients in the Regional Infectious Containment Unit (RICU). "They were actually dying really fast, [and there was] nothing we could do," she says.

She recalls a patient who was being weaned off of a ventilator: "He was maxed out on oxygen support. … A lot of his organs were failing. We had exhausted all possibilities." She FaceTimed with each of his immediate family members (see "Saying Goodbye").

"Normally we would give the family member time and space, close the curtain, and allow them to be at the bedside. Since the pandemic, we're the ones who are in there with the raw emotion of the family." An exception to the no-visitors policy was made for end-of-life visits, but some families did not want to take the risk of entering a unit with many COVID-19 patients. When patients couldn't be with their family members, Shokar and other RICU staff made sure no one died alone. "We are at the bedside and holding their family member's hand."

The patient was unconscious, and his family members said goodbye to him via FaceTime while Shokar held the phone. Then he was taken off life support, and Shokar waited with him for his last hour and a half. She wishes she could have done more. Even hand holding in the RICU can only approximate the closeness one might wish for at the end of life. "They're still not feeling skin-to-skin contact. They're feeling our gloved hand."

Shokar takes solace in the relationships she's formed with her colleagues. "We try to stay positive, even though we've been through so much. We've laughed and cried together." On her days off, she gives other nurses facials in the hotel room where she's staying. "Front-line facials," she calls them.

"The support we've given each other is indescribable. I don't think anybody will understand the bonds that we now have for life because of the pandemic."

BETTER TOGETHER

"I had not met Ross before this. Then we began working side by side. A lot of people who would normally be in separate silos came together, and we came up with best practices. You don't want anyone but the most experienced operators intubating these patients or handling tracheostomies. If we had an airway emergency, we were literally sitting next to an anesthesiologist, and if a team wanted to review chest imaging or discuss pulmonary pathophysiology, our pulmonary intensivists were right there. Nephrology, Infectious Disease, Palliative Care, ENT, and so many more teams were all part of this effort. This has worked extremely well, and I hope that this ability to be nimble and work together more easily is one lasting result."

—Jake McSparron, M.D., assistant professor of internal medicine with a focus on pulmonary and critical care medicine. He co-directed the RICU with Ross Blank, M.D., assistant professor of anesthesiology.

"We had 50 COVID patients at our max in the RICU. Most ICUs are typically 20 to 24 patients on a floor, so having 50 is unprecedented. The only way to take care of all of these patients was to bring in a lot of intensivists — anesthesia intensivists, surgeon intensivists, neurology intensivists, and others as well. We had this multi-departmental team all working side by side to take care of the patients. It worked because it was an emergency situation, and Jake and I were able to quickly get along very easily and be practical about making a functional team. I have really been impressed by the relative seamlessness of people from different units working together on teams. I would like to think that is something that will be continued into the future."

—Ross Blank, M.D., assistant professor of anesthesiology and a co-director of the RICU

NURSING EXECUTIVE: "WHEN A CRISIS OCCURS, WE RISE"

' 200: The number of nurses who volunteered during a 48-hour period to staff a unit that would care for COVID-19 patients.

' 107 to 267: The increase in the number of ICU beds after many areas were converted to treat COVID-19 patients.

' 10,000+: The number of calls accepted through the COVID-19 Hotline since March 15.

' 15,000+: The number of reprocessed N95 masks used at Michigan Medicine by mid-June.

Nancy May, DNP, RN-BC, NEA-BC, is proud of those numbers, which tell some of the story of how hard nurses have worked during the COVID-19 pandemic. "When a crisis occurs," says May, the chief nurse executive for Michigan Medicine, "we rise."

May praises the nurses who helped to set up and run the Regional Infectious Containment Unit (RICU) — particularly Julie Juno, RN, and MaryAnn Adamczyk, RN, who were the co-clinical nursing directors of the unit, where some of the sickest COVID-19 patients were treated. The entire nursing model had to change during the pandemic, May says; for example, the usual one-to-one or one-to-two nurse-to-patient ratio in ICUs was replaced by a ratio of three ICU nurses, a moderate care nurse, and a tech per 10 patients.

"Our nurses stood up and did things I never thought we'd be able to do. Responding to COVID-19 has not been an easy lift," May says. "It's humbling to me to see how far we've come, and how we pulled together as a community of nurses."

It wasn't just the nurses in the RICU and other ICUs who stepped up during the pandemic, May is quick to point out. Nurses in all areas of Michigan Medicine were impacted with temporary assignments, new training protocols, adjusting to telehealth, and much more. To the nurses, she says:

"You'll look back and reflect on this and think, how did we do it? You did it because you're a Michigan nurse, and you know what we can accomplish together.

"I know we'll be stronger because of it."

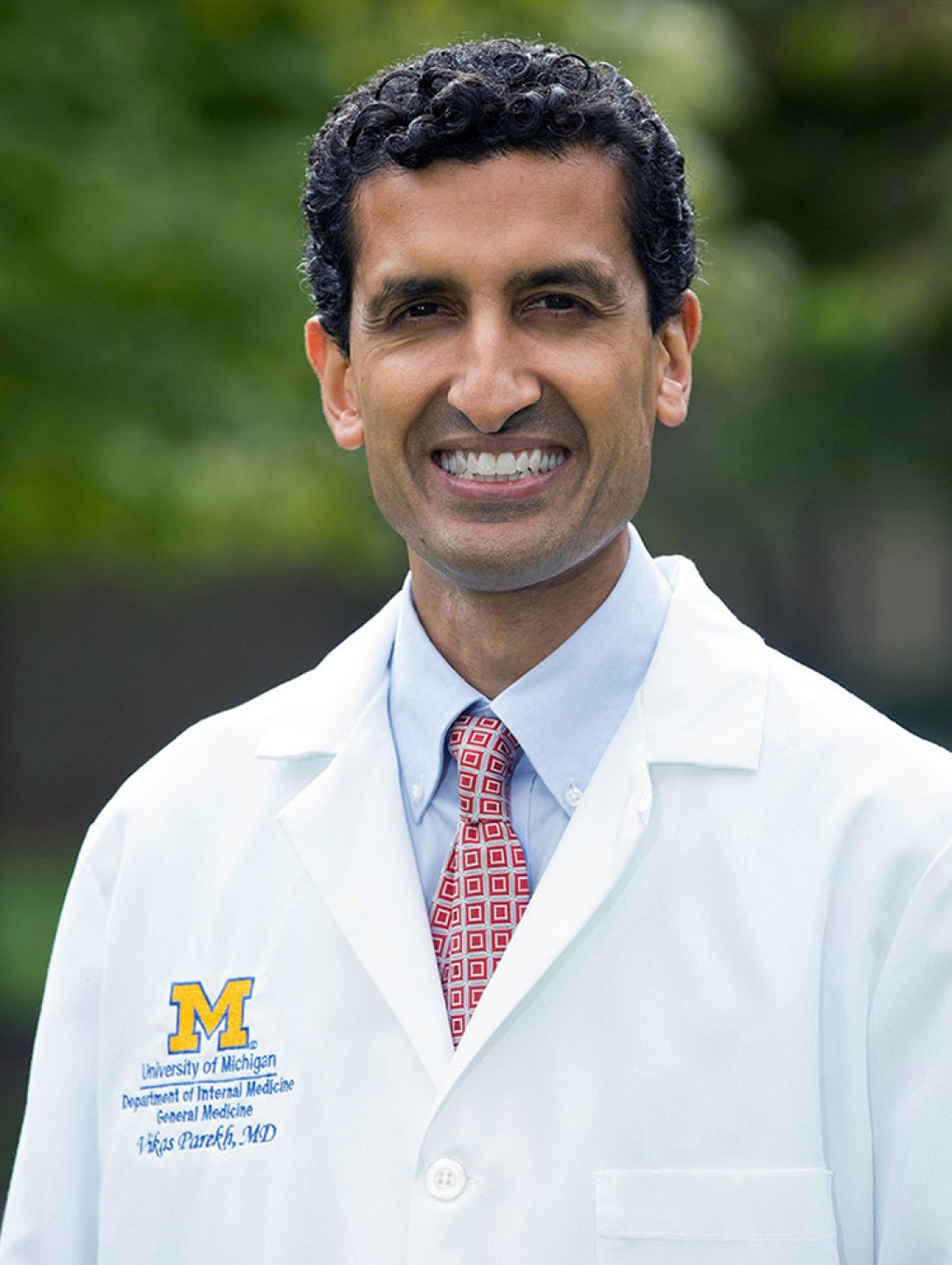

THE NUMBERS GUY

On April 14, the curve had flattened at Michigan Medicine. At least, it looked that way to Vikas Parekh, M.D. (Residency 2002). Parekh was up and ready by 7 a.m., beginning his workday with his new ritual: looking at the Michigan Medicine COVID-19 data. As associate chief clinical officer for medical services, Parekh had been pulled off clinical duties so he could lead Michigan Medicine's analytics and operations. He stayed on top of data predictions and helped to inform organizational decisions based on changing numbers. He reported the numbers each morning at an 8 a.m. huddle with other front-line staff.

Before early April, cases were rising exponentially in southeast Michigan. By mid- April, it appeared that Michigan's social distancing efforts were paying off. On this day, there were 225 COVID-19 inpatients at Michigan Medicine, down from a high of 229 on April 8. "From the beginning I said, 'I wish we were wrong.'" That Tuesday, Parekh finally had a chance to share good news not only with his colleagues, but also with state legislators.

At lunchtime, Parekh and his team met with the state Senate majority leader, House speaker, and their staff. Then he attended a daily update with hospital physicians and nursing leadership. After that, it was the 3 p.m. huddle, followed by a TV interview with WDIV-Local 4 News in Detroit.

By the evening, he'd had a very busy day, but he hadn't stepped foot outside his house. Adhering to social distancing guidelines, Parekh conducted all of his meetings virtually that day. He has a home office, but "I camp out in our dining room," he says, where he shares space with his two kids, ages 9 and 12, whose school building closed due to the outbreak.

In addition to his professional duties, Parekh was also on duty at home, helping his kids navigate the new realm of virtual learning. His wife is a pediatric cardiologist at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, and she was working on site that week. "My kids are pretty self-directed," he says. "Most of what I have to do is technology troubleshooting."

After the kids were both in bed, Parekh was back at work, preparing a presentation for a meeting with the governor's executive staff the following morning. From his home office, Parekh would give the state's top elected official guidance for when to let up on stay-at-home orders.

"THE HUMAN STORY"

Andrew Rosenberg, M.D. (Fellowship 2000, Residency 2002), associate professor of anesthesiology and chief information officer for Michigan Medicine, speaking on May 8.

"I would never have thought about talking about withdrawing critical care with a family over the phone. Now we are doing it with FaceTime when they can't come into the ICU. One of the things that makes this time so different, so special, that is seared in my memory, are the human stories. We withdrew on two patients today. At least today, the families could be here.

"An adult son and his wife huddled next to each other, holding their hands, looking down at their laps, with their n95 masks that they brought in from home, with his mother, on a ventilator with a new trach tube in place. Her eyes were closed, and she was comfortable. She was 62, and she died today. Other patients, on ventilators, on nitric oxide, who can only barely be oxygenated lying prone (on their stomach). Those are the images of COVID for me.

"There is a sense of isolation in the RICU [Regional Infectious Containment Unit] now. The patients are isolated from their loved ones. The caregivers are isolated from the patient and their family. The caregivers are isolated from each other. This is isolation that goes on. I decided to self-quarantine at home. I sleep downstairs and my family and I eat at different ends of the dining room table.

"We are having to use leather restraints with some patients. The security team came with leather restraints. We have a young guy and he can't be adequately sedated. He's on five separate drips, each of which would be enough to sedate a normal patient. He is 27. We never use leather restraints in the ICU. There is some incredibly tough delirium that can come from COVID.

"Those of us who worked in the RICU, we're all from different parts of Michigan Medicine. We had teams being formed that have never worked together. We opened up new spaces. If there is one thing that I think will be enduring, it's how to create these multidisciplinary teams. People are exchanging ideas with each other. It's extraordinary, what we can accomplish together."

THE SOLDIER'S CREED

"I am a warrior and a member of a team."

This is the beginning of the U.S. Army Soldier's Creed, which Kevin Ward, M.D., has recited to himself each day during the COVID-19 crisis. His use of the creed to psych himself up for a difficult mission makes sense; Ward — a professor of emergency medicine and director of the Michigan Center for Integrative Research in Critical Care (MCIRCC) — is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve Medical Corps as well.

Every part of Ward's multifaceted job has been critical to the COVID-19 response at Michigan Medicine. As an emergency medicine physician, he has worked many clinical shifts, during which he and colleagues assessed whether patients were COVID-19-positive while still tending to the usual broken bones, heart attacks, and infections. "We have the only ICU in an ED in the country," Ward says, referring to the Joyce and Don Massey Family Foundation Emergency Critical Care Center, or EC3. "We're fortunate that we can get critically ill patients in the emergency room quickly and move them to this area, where we can isolate them from the rest of the department."

"I will never accept defeat."

Other days, he has spent countless hours on Zoom video meetings for department conferences, meetings with residents, and the efforts of the 150-member MCIRCC. While some laboratory research throughout U-M halted during the peak of the first wave of the pandemic, MCIRCC's work had never been more vital.

"We already had research on sepsis and ARDS [acute respiratory distress syndrome], which is what people with COVID-19 are dying from," says Ward. "We were able to pivot quickly to some valuable research related to COVID."

"I will never quit."

MCIRCC teams are using previous work that identified breath signatures in ARDS patients to identify signatures in COVID patients to better understand the disease and help develop new ways to track the disease's progression. In collaboration with FlexSys Inc., an Ann Arbor company and U-M startup, MCIRCC developed a new, portable, and mass-producible helmet and tent system that has the potential to transform any hospital space into a negative-pressure environment. The helmet and tent placed on patients protects caregivers and could be used to provide therapies that may spare ventilators for many critical cases as well as to allow for procedures like intubation, tracheostomies, and bronchoscopies with greater safety.

"This is where the innovation highway meets the commercialization highway. From the Autobahn, to 10 m.p.h.," Ward says. "Our challenge now is trying to identify partners with manufacturing capabilities and supply chains as well as navigating the FDA in order to make these innovations available. We are working closely with our colleagues in the U-M Office of Technology Transfer to move things forward as quickly as possible. This is as much about protecting providers as it is about patients. If the providers don't get sick, then you're not taking those warriors out of the battle."

"I will never leave a fallen comrade."

Ward has been impressed with fellow physicians and researchers, as well as nurses, respiratory therapists, and other providers. "Some of my heroes have been the custodial staff," he says. "They meticulously clean every room and make it easier for us to move in and out. They are really unsung heroes."

He admires the way everyone at Michigan Medicine and other colleges, schools, and units at the university, such as the College of Engineering, has pivoted to the sudden and massive changes that were needed to treat influxes of COVID-19 patients. "People were able to step out of their comfort zone. Everyone is ready to help. That's gratifying, this team mentality that permeates the institution," Ward says.