Researchers have shown how tumor-associated macrophages release compounds that block gemcitabine in the most common type of pancreatic cancer

2:55 PM

Author |

A frontline chemotherapy drug given to patients with pancreatic cancer is made less effective because similar compounds released by tumor-associated immune cells block the drug's action, research led by the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center found.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

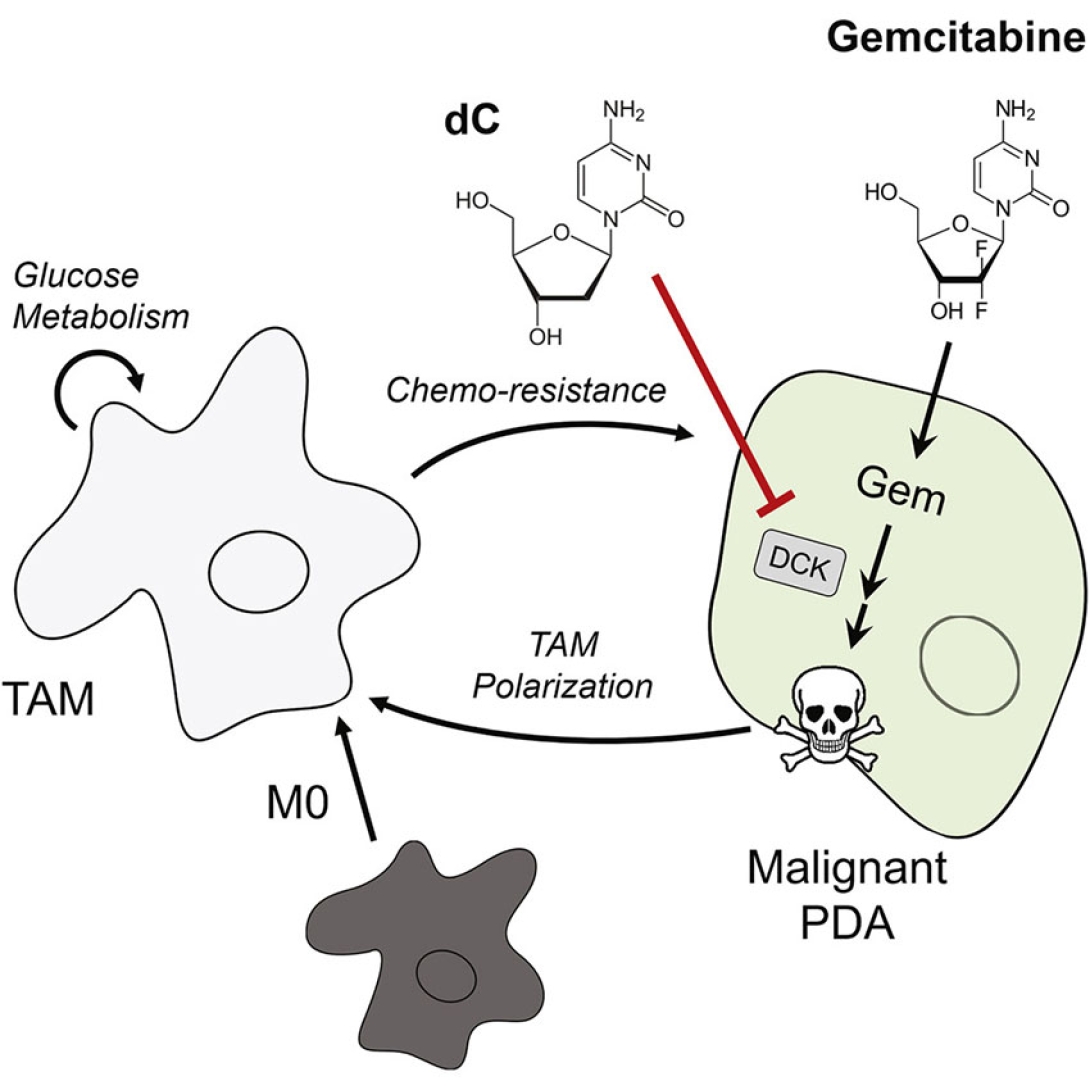

The chemotherapy drug gemcitabine is an anti-metabolite. It's similar to normal metabolites taken up by the cell, but once inside it kills the cell by disrupting its functions — like a Trojan horse. In pancreatic cancer, tumor immune cells release metabolites that are nearly identical to gemcitabine, and these block the activity of the drug in malignant cells, the researchers found.

Why does gemcitabine work pretty well in some cancers but not in pancreatic cancer, that's the big question my lab was trying to answer,Costas Lyssiotis, Ph.D.

These insights could be used to predict which patients will respond to gemcitabine therapy, as well as shed new light on other types of cancer where immune cells may be playing an important role in resistance to chemotherapy, according to findings published recently in Cell Metabolism.

"Why does gemcitabine work pretty well in some cancers but not in pancreatic cancer, that's the big question my lab was trying to answer," says study senior author Costas Lyssiotis, Ph.D., assistant professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology at the U-M Medical School.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal types of cancer. It's typically aggressive and doesn't respond well to traditional chemotherapy and radiation treatments. And although progress has been made in recent years, five-year survival rates are still in the single digits.

"Malignant cells often only make up about 10 percent of a tumor," says study first author Christopher J. Halbrook, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in the Lyssiotis lab. "The remaining 90 percent are other types of cells that support the growth of that tumor — like structural cells, vasculature, and immune cells. Our work has been focused on the interaction between malignant cells and immune cells."

Large contingents of immune cells known as macrophages are often found in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the most prevalent type of pancreatic cancer. And while macrophages were known to prevent the activity of gemcitabine chemotherapy, exactly how the immune cells did this had been unclear.

Lyssiotis and his collaborators at U-M and in Scotland investigated the interaction between malignant cells and tumor-associated macrophages, finding the immune cells released a host of compounds known as pyrimidines, which are metabolized by the malignant cells.

One of these compounds, deoxycytidine, has a chemical structure that's very similar to gemcitabine and directly blocks the activity of the chemotherapy drug in the malignant cells.

"Deoxycytidine basically outcompetes gemcitabine," Lyssiotis says, adding that the physiological reason underlying the immune cells' release of the pyrimidines is still unclear.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

After genetically and pharmacologically depleting the number of tumor-associated macrophages in mouse models, the team showed that the tumors were less resistant to gemcitabine — offering a clue toward potentially making patients' tumors more responsive to chemotherapy.

The researchers also looked at data from patients with pancreatic cancer and found that patients whose tumors had fewer macrophages had responded better to treatment.

"When we think of personalized medicine, we often think about what's going inside of the malignant cells, what specific genetic mutations a patient's tumor may have," Lyssiotis says. "In our case, we're thinking about, 'What does this tumor look like as a whole? What does its ecosystem of cells look like?' And hopefully we can use an understanding of the interaction between different types of cells to develop new approaches to treatment."

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!