Researchers expand the use of ribosome profiling, also known as Ribo-seq, to understand protein production in cells

8:51 AM

Authors |

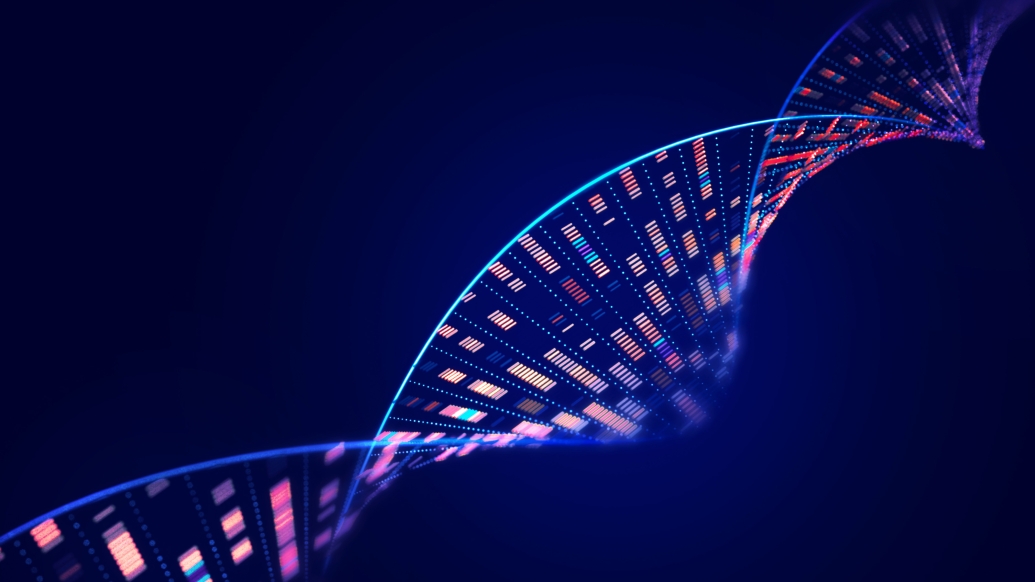

A gene sequencing method called ribosome profiling has expanded our understanding of the human genome by identifying previously unknown protein coding regions.

Also known as Ribo-seq, this method allows researchers to get a high-resolution snapshot of protein production in cells.

Ribo-seq has the potential to advance cancer research, but many of the discoveries enabled by Ribo-seq provide an untraditional view of where and how protein production might happen.

As such, scientists must first verify these regions code for proteins.

A tool for cancer research

“Ribo-seq has garnered major interest for use in studying protein production in cancer cells to identify a specific abnormal proteins as targets for immunotherapy or other treatment approaches,” said John Prensner, M.D., Ph.D. an assistant professor in the University of Michigan Medical School Departments of Pediatrics and Biological Chemistry.

Immunotherapy treatment activates the patient’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells. It lacks the toxic side effects of chemotherapy like nausea, vomiting and hair loss, making it a highly desirable treatment for patients that qualify.

SEE ALSO: Immunotherapy: The Future of Cancer Treatment

Currently, immunotherapy is only available for certain cancers.

Tumors that produce a large number of proteins with easily identifiable mutations are compatible with immunotherapy.

Drugs have been developed to target those proteins to unleash the immune system against cancerous cells.

Scientists hope to use Ribo-seq as a tool to understand the proteins cancer cells produce to expand immunotherapy’s success to a larger number of cancer patients.

Investigating protein machines

Producing a protein requires two steps – transcription and translation. Ribo-seq zeroes in on the second step of translation.

During transcription, the cell takes the DNA master blueprint and makes a copy of the genetic instructions known as messenger RNA or mRNA.

The messenger RNA is then shuttled over to a ribosome, a tiny protein factory within the cell, to start the process of translation.

The ribosome translates the instructions to link amino acids together to form a protein.

In the past, researchers have used RNA sequencing or RNA-seq to identify genes that are activated to make proteins in a given tissue sample, says Prensner.

For example, RNA-seq could be used to identify which genes a cancer cell is using to make proteins and identify any mutations in those proteins.

RNA-seq is a proxy for the process of translation, but there are multiple factors that can alter results. Ribo-seq analyzes the translation process, giving a clearer picture of the rate and location of translation.

Collaboration to improve databases

When scientists first get back the results of any genetic sequencing, to make any sense of the long list of letters, they must align the genetic sequence to a reference genome.

Reference genomes are a digital database of an accepted representation of an organism’s gene sequence.

If a scientist is studying cancer biology in the human genome, they would use a human genome reference sequence as a standard comparison to the gene sequence generated in their study to learn more about function.

Currently, human genome reference databases are not well equipped to recognize Ribo-seq results. The lack of standardization inhibits Ribo-seq’s use for the global research community.

To remedy this, Prensner, whose lab focuses on the molecular basis of pediatric brain cancers, teamed up with an international group of researchers to begin a project to improve human genome reference databases for Ribo-Seq use.

During Phase I of the project, this team of research organizations produced a standardized catalog of 7,264 Ribo-seq Open Reading Frames – spans of DNA fragments that code for proteins – which is made freely available to scientists worldwide. Although a good start, this catalog requires additional scrutiny to answer a critical question for the research community: how many of these Open Reading Frames truly produce a protein product?

Cross-checking results

Prensner led a research effort to integrate Ribo-Seq and proteomics techniques, laboratory methods to confirm the presence of a protein within a cell, to increase researchers’ confidence in whether these Ribo-Seq Open Reading Frames produce proteins.

The results are published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

The research team proposes a framework to standardize levels of evidence for these newly identified protein-coding regions.

Classifications vary from “protein candidate” with the strongest required supporting evidence to “detected” with the least required supporting evidence.

“We believe this common terminology and shared database resources will reduce confusion and improve the precision of research on these Open Reading Frames identified by Ribo-Seq,” said Prensner.

Improved databases will support more accurate gene sequencing interpretations and foster insights in cancer as well as across all aspects of human biology for years to come.

Paper cited: “What can Ribo-seq, immunopeptidomics, and proteomics tell us about the non-canonical proteome?” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. DOI: 0.1016/j.mcpro.2023.100631

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!