A child with facial differences might initially turn heads, but there are ways to ensure a smoother time at school. A pediatric social worker offers tips.

7:00 AM

Author |

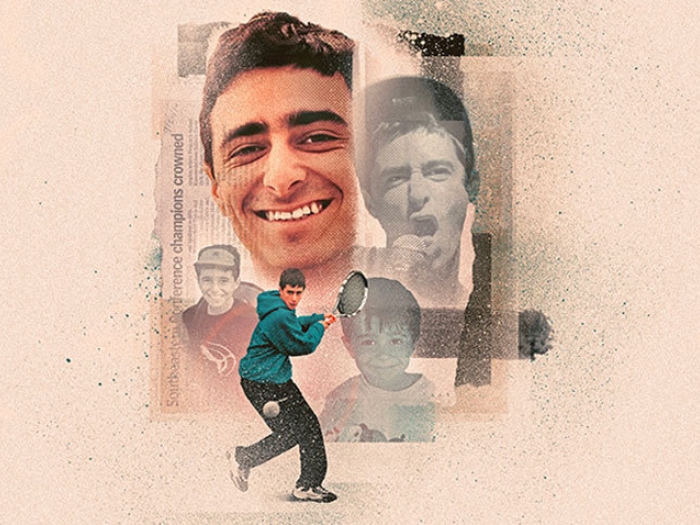

Children with craniofacial anomalies already have their share of unique challenges.

Feeling comfortable around other kids shouldn't be one of them.

SEE ALSO: 5 Signs Your Child Might Have Vision Problems

For some young people with conditions such as a cleft lip or craniosynostosis, the start of a new school year could mark the first time they've been left to explain their health differences without a parent or guardian nearby.

Some kids may worry about teasing or isolation from others who at first fear their appearance, so taking steps to prepare for various scenarios is important.

"Education is the first and best defense," says Laura Hatch, L.M.S.W., a clinical social worker for the University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

Helping boost awareness is Craniofacial Acceptance Month, which occurs annually in September to recognize the many individuals with one of the most common forms of birth defects. More than 130,000 babies worldwide are born yearly with clefts of the lip or palate alone.

Hatch, who counsels patients and families in the Craniofacial Anomalies Program at U-M, offered tips both for affected kids and their classmates meeting each other for the first time.

Start a conversation: Some children — or families of those — with such anomalies or their families might send a brief note or introduce the young person to their peers before the start of practice, club meetings or a new school year.

SEE ALSO: The Healing Power of Hospital Dogs

Giving other kids a heads-up "takes away some of the surprise," Hatch says. "Everyone accepts it and moves on. It shows that there's nothing to be afraid of."

Embrace respectful questions: It's natural for kids to want to learn more about someone who doesn't look exactly like them. Questions such as "How did that happen?" and "Does it hurt?" if asked kindly, should be welcomed. A child with abnormalities might consider bringing in X-rays or a piece of medical equipment for perspective.

Parents of affected children, meanwhile, ought to help them prepare responses to potential questions they feel comfortable answering.

Avoid conflict: Teasing, while painful, isn't unlikely. Children who fall victim to harsh words ought to be ready with a rebuttal — "It hurts my feelings when you tease me," Hatch suggests, or "I really don't have time for this" — or plan to simply walk away.

Families of peers should also educate their kids about the value of empathy via dinner-hour discussion or popular media. The main character of a best-selling tween book series, for example, is a boy with facial differences.

Embrace the whole kid: Although one's looks could be the focal point of early dialogue, the individual (plus his or her classmates) needn't always treat it that way.

Children with facial differences should tout enjoyment of and, when able, participation in the same hobbies as others — whether it be athletics, academics or the arts. Sharing that connection can help spark and sustain friendships, Hatch says.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!