James Gerrit Van Zwaluwenburg (M.D. 1908) was an early adopter of X-ray technology, and he made imaging an integral element of clinical diagnoses and patient care at U-M.

Author |

In the latter part of 1921, the doctor's friends saw that his astonishing devotion to work was putting his health at risk. If he wouldn't stop for a rest, they warned, he at least had to slow his pace, even if just a little.

He admitted he'd been pushing himself too hard for too long — certainly since he'd led Michigan's roentgenology efforts beginning in 1913. Actually, he'd been doing this ever since medical school, when he'd impressed the Michigan faculty as perhaps the most brilliant student they'd seen.

"He knew the risk he was running," said his colleague Reuben Peterson, M.D. "But something this important drove him on, regardless of the cost."

For years, the doctor had been so busy with the department's day-to-day affairs that he'd had too little time for his own research. Even so, at just 46, he'd already made a major mark, with pioneering work in tuberculosis; in the X-ray location of foreign bodies in the eye; in cardiac measurements.

He was as familiar to his colleagues as a brilliant and caring brother, unfailingly making time to help when asked.

Now he was glimpsing the outline of his most ambitious work: a full-length monograph on peritoneal pneumography. In a storm of labor, he blocked out the entire book, chapter by chapter.

Then, at the beginning of January 1922, he was suddenly very sick. The diagnosis was acute pneumonia. He checked himself into University Hospital.

U-M's First Radiologist

James Gerrit Van Zwaluwenburg (M.D. 1908) was born in 1874 near Zeeland, Michigan, in the heart of the Dutch-American enclave founded by Calvinist emigrants. When his parents sold their farm, there was enough cash to help him pay for preparatory work at Hope College. In his final year there, Van Zwaluwenburg taught chemistry to help cover his tuition. He entered U-M as a sophomore, and his professors remarked on his extraordinary mind and ferocious work ethic.

Van Zwaluwenburg had always wanted to become a doctor, but there was no money for medical school. So for five years he earned his living as a metallurgical chemist, saving what he could for tuition. By 1903 he was back in Ann Arbor for medical training and was soon appointed as a "demonstrator" in anatomy, dissecting cadavers as junior students watched. He developed an uncannily detailed memory of the human body's intricate structures — knowledge that would serve him well.

When he graduated, the great internist George Dock, M.D., asked "Van," as everyone called him, to join the faculty as an instructor in internal medicine.

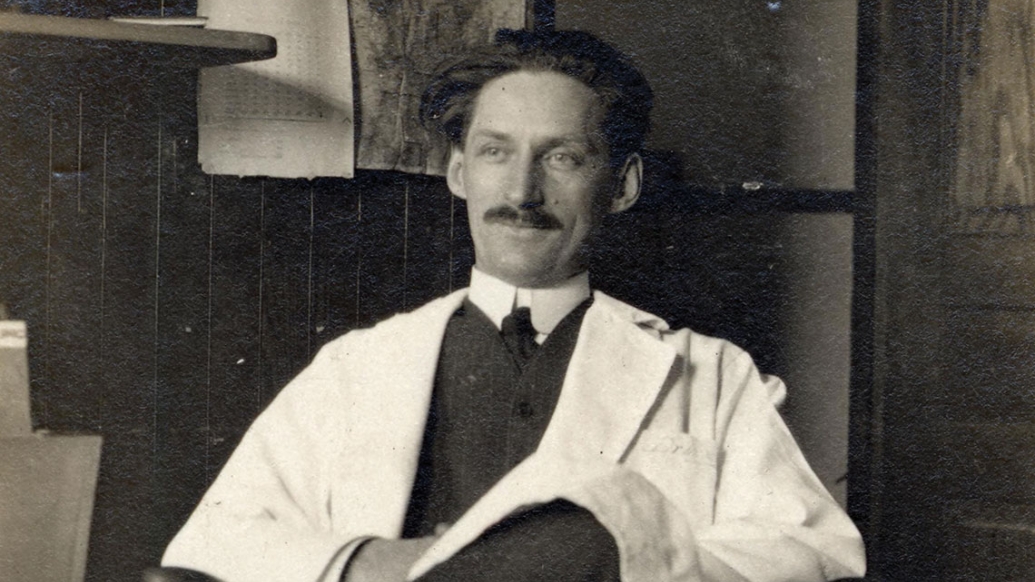

He made a fierce first impression — thick hair swept back; intense gaze; a manner of utter frankness. He was quite unlike the surgeon Hugh Cabot, M.D., the epitome of the Harvard-trained Boston Brahmin and later dean of the Medical School. But Cabot quickly saw Van's quality. "Lean, lank, and uncouth in appearance," Cabot said, "there was nothing either lean or uncouth about his personality."

He married and had children, but if ever a doctor was married to his work, it was Van Zwaluwenburg, who bought a house on Cornwell Place, practically next door to the hospital buildings on Catherine Street.

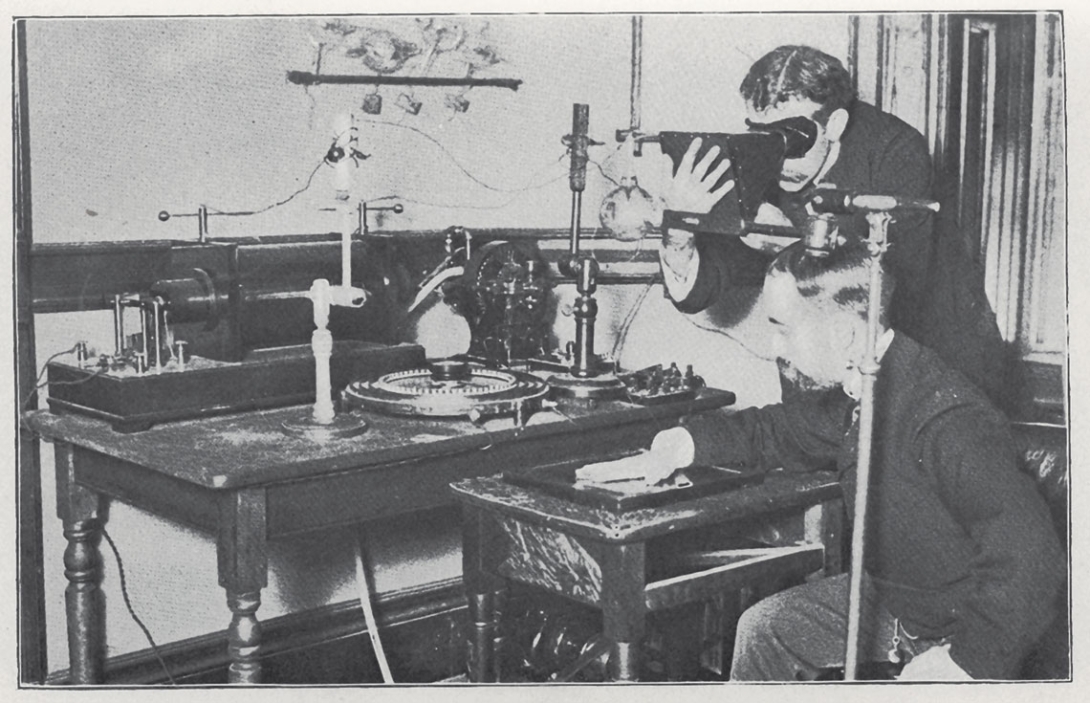

Soon Albion Hewlett, M.D., Dock's successor, asked Van to help him study the heart's architecture using X-rays — the new technique known as roentgenology. Van leapt on the project. He quickly mastered the technology and amassed hundreds of X-ray plates, making a major contribution to estimating a heart's volume.

He was seeing a new science blossom, and "once lighted," a friend said, Van's enthusiasm for X-rays "was inextinguishable." He was appointed assistant professor of roentgenology — U-M's first radiologist. Then, in 1917, the regents authorized him to organize a Department of Roentgenology and named him its chair.

The Voice of Authority

With X-rays revolutionizing diagnoses, other departments deluged him with requests for imaging examinations, and his workload soared. He responded by becoming a superb executive. He used dictaphones and insisted on sending typewritten reports to referring departments. He devised a filing system that made any X-ray instantly retrievable. He kept charges low but made the service pay.

He was as familiar to his colleagues as a brilliant and caring brother, unfailingly making time to help when asked. "It was not by chance, or because his name was hard to spell or pronounce, that he was 'Van' to all of us," one said. "We addressed him thus because we loved, admired, and respected him."

Colleagues thought he had the ideal scientific mind: always restless in the search for more data, keenly critical in analyzing another's views, but always open to the possibility of error in his own analysis. "It was so customary to ask what Van's diagnosis was, no matter how special the field or intricate the problem," Peterson said, "that the clinical staff took it as a matter of course, only occasionally thinking of the many hours of study, the scientific interest, and the keen and comprehensive mind necessary for such accurate diagnostic skill."

He had no hobbies, only his fascination with his work. Once, at a train station, Van and Augustus Crane (M.D. 1894), a radiologist from Western Michigan, got into a fierce debate about the best method of measuring heart volume. The arrival of Van's train cut the discussion short. Several days later, Crane received a letter from Van — "five long, closely spaced, typewritten pages in which he explained his position with such force, breadth of view, and unquestioning friendship that I was deeply impressed." It was so persuasive that Crane later sent it to a medical journal for publication.

That habit of going the extra mile sometimes concerned his colleagues. As dean, Cabot learned to curb his urge to ask him for help. He knew Van would work himself to exhaustion before saying no.

A Life Cut Short

In the hospital in 1922, he lasted only a few days, and died on January 5 at age 48, his book unfinished. "How can we replace him?" colleagues asked. A year later, gathering to remember him, they were still stunned by the loss. Preston Hickey, M.D., who would succeed Van Zwaluwenburg as chair of radiology, said: "We cannot help feeling that some blind fate or inscrutable providence tore him away from his life work scarcely begun."