Inside U-M’s varied approaches to fighting the epidemic, including innovations in both prevention and treatment — and why there might be “great reason for hope.”

Author |

The questions are seemingly infinite: What makes one person more prone to addiction than another? What is the right number of pills to prescribe after a knee replacement, a mastectomy, or a C-section? How can we prevent teens from trying these drugs, and short-term users from developing a substance use disorder? What can be done about the scourge of ultra-powerful synthetics?

We know how the opioid epidemic began. But how does it end?

Researchers and clinicians at the University of Michigan are seeking answers on a multitude of fronts. It's impossible to solve the public health crisis born from the overuse of this powerful pain medicine alone, but together, they are making an appreciable dent in the ways that opioids are prescribed, used, disposed of, and understood. They are making strides in the treatment of addiction, as well as the prevention of substance use in the first place.

No single story can highlight all of the opioid-related work being done at Michigan Medicine, but this article encompasses many pieces of the opioid puzzle: from policy to practice, from pediatrics to geriatrics, from prescriptions to street drugs, from addiction to recovery. What follows can shed light on some of the emergent and urgent projects that offer reasons to believe current trends can be reversed, or at least slowed. "We are in a serious crisis," says Frederic C. Blow, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and director of the Addiction Center and the Substance Abuse Program at Michigan Medicine. "But I think there's great reason for hope."

Over Dosing and Over Prescribing

Beginning in the early 2000s, opioids were increasingly used to treat chronic pain in the U.S., Amy Bohnert, Ph.D., and Mark Ilgen, Ph.D., point out in a 2019 review article in The New England Journal of Medicine. The change came in response to "concerns about the undertreatment of pain, new clinical guidelines, and the declaration by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations of pain as the 'fifth vital sign,'" wrote Bohnert, associate professor of psychiatry, and Ilgen, professor of psychiatry and director of U-M's Addiction Treatment Services.

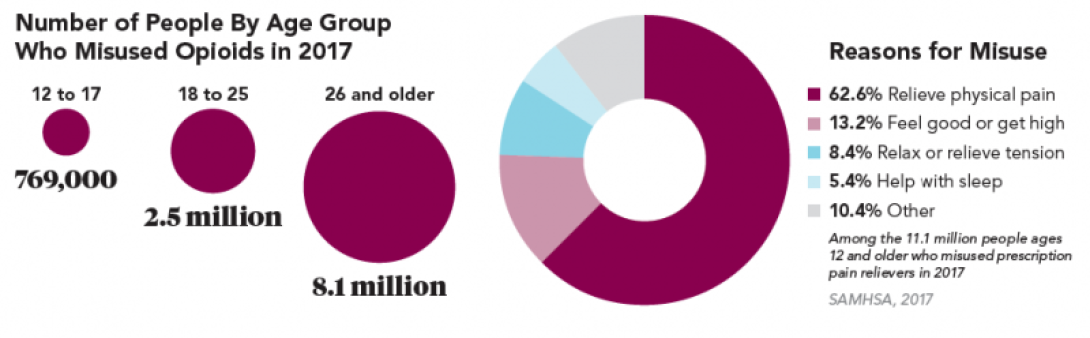

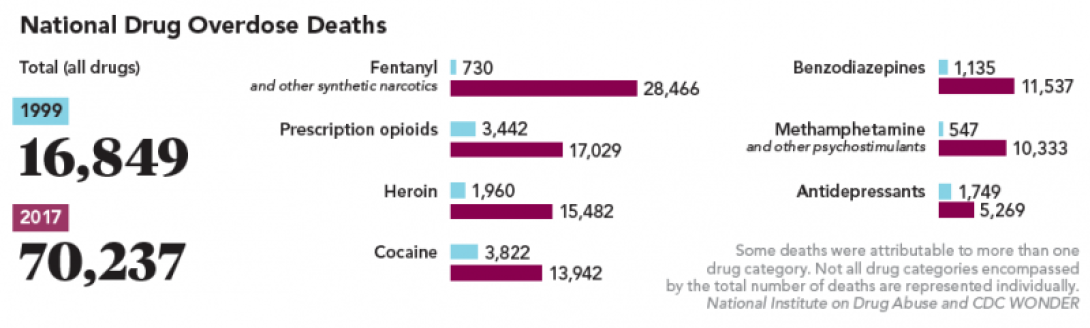

As a result, the average dose of prescribed opioids increased from about 100 to 700 morphine milligram equivalents per person, per year, between 1997 and 2007. The increased availability of opioids — due to prescriptions and influxes of manufactured synthetic opioids such as fentanyl — likely formed the basis for a spiral of overuse and misuse. The result for many has been deadly: Bohnert and Ilgen's analysis showed that suicides and drug overdoses kill American adults at twice the rate today as they did just two decades ago, and opioids are key to that statistic.

They propose several interventions:

'' That people who are on high-dose regimens of prescription opioids, or those who are showing signs of prescription misuse, receive care that includes slow, patient-centered tapering of opioid use;

'' that the number of opioids prescribed be reduced when other pain treatment strategies with a better risk profile or that are more effective can be used instead;

'' that providing the medication naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose, be prioritized for friends and family of those at high risk of overdosing;

'' and that medications for opioid use disorders be made more widely available.

One of the goals — reducing the number of opioids that are prescribed — is the intent of Michigan OPEN, the Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network. Members of Michigan OPEN developed a tool that recommends the specific number of opioid pills that should be prescribed after 25 common procedures (for example, 50 oxycodone tablets are recommended for total knee arthroplasty, while 10 are recommended for hernia repair). The numbers are based on the maximum opioid use reported by 75% of patients who have had that surgery. The OPEN team's research has found that many surgeons write prescriptions for opioid pain medications four times larger than what their patients will actually use. They also found that the number of pills in the prescription may be the most important factor in how many opioid pills the patient will take.

"We've told people in the past, 'If you have real pain, you won't become addicted.' We know how wrong that is now," says Chad Brummett, M.D. (Residencies 2006), associate professor of anesthesiology, director of the Division of Pain Research in the Department of Anesthesiology, and a co-director of Michigan OPEN. "We also know that the more opioids I give you, the more you'll take."

Yet Brummett and his colleagues are well aware of the concern among surgeons and pain patients that smaller prescription sizes will lead to greater problems with pain.

The researchers emphasize that they don't want patients to be in pain; indeed, they point out, research suggests that patients' pain scores remain unchanged even when they are given fewer opioids. A groundbreaking 2017 study from the OPEN team found that some surgeons might be able to prescribe one-third of the opioid pills they currently give patients and not affect their level of post-surgery pain control. That would mean far fewer opioids left over to feed the ongoing national crisis.

"We continue to notice that with education and attentive care, fewer and fewer opioids are needed and pain care is improving," says Michael Englesbe, M.D. (Residency 2004), the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., M.D., and Cyrenus G. Darling Jr., M.D., Professor of Surgery; program director of the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative; and one of the authors of the study. "Our ambitious goals include empowering half of the surgical patients at Michigan Medicine to be opioid-free following the first day of surgery."

Michigan OPEN is co-directed by three Michigan Medicine physicians: Brummett; Englesbe; and Jennifer Waljee, M.D. (Residencies 2009, 2011, and 2012), MPH, associate professor of surgery. It launched in 2016, with support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation (IHPI) at U-M. The partnerships have bolstered the awareness and adoption of OPEN's recommendations, Brummett says. Now, other states are looking at Michigan's model to implement their own guidelines. "Nobody is doing this on the scale that we are. Others are following our lead," he says.

"The opioid epidemic in our communities does not discriminate by race or socioeconomic status. I have seen firsthand that this medical illness affects everyone — rich, poor, rural, urban, educated, uneducated, young adolescents, and elderly adults." —Rebecca Cunningham, M.D.

Opioid Solutions

In 2015 and 2016, for the first time in half a century, life expectancy in the U.S. declined for two consecutive years; a key factor was the increase in unintentional injuries, which includes overdose deaths.

Opioid Solutions, a resource developed by the U-M Office of Research, the Injury Prevention Center, and IHPI, is trying to understand an epidemic partially responsible for the decline. It serves as a central hub for research, educational activities, and community outreach related to opioids, and draws on nearly 100 U-M faculty — in fields ranging from psychiatry, pharmacy, and public policy to basic science and law — whose research explores opioid misuse and overdose.

"The opioid epidemic in our communities does not discriminate by race or socioeconomic status," says Rebecca Cunningham, M.D. (Residency 1999), professor of emergency medicine, director of the Injury Prevention Center, and associate vice president for research within the Office of Research at U-M. Cunningham studies opioid overuse and overdose from both the clinical and policy perspectives. "I have seen firsthand that this medical illness affects everyone — rich, poor, rural, urban, educated, uneducated, young adolescents, and elderly adults."

A separate cohort of bioscience researchers at the university's Edward F. Domino Research Center, housed in the Medical School's Department of Pharmacology, is exploring opioid addiction at the molecular and cellular levels. The center, led by John Traynor, Ph.D., the Edward F. Domino Research Professor of Pharmacology, aims to understand the addiction process through neuroscience and animal behavior, to identify medications to treat opioid abuse and overdose, and to design non-addictive pain medication.

"A basic science approach is critical when addressing a crisis as serious as opioids because it provides us all with a better understanding of how to manage pain effectively and safely," said Traynor, also a professor of medicinal chemistry in the College of Pharmacy and associate chair of research in the Department of Pharmacology.

Additionally, opioid prescribing is the first focus of the new U-M Precision Health initiative, which spans 19 colleges and schools. Precision Health will focus on building capabilities, including data sets, tools, and resources that researchers can use to facilitate collaborative work, says the initiative's co-director, Sachin Kheterpal (M.D. 1999, Residency 2008), associate professor of anesthesiology and associate dean for research information technology in the U-M Medical School.

"One of the things to address the opioid misuse crisis is an opioid prescribing strategy that is a precision prescribing strategy," Kheterpal says. "It's not the only thing — there's a ton of treatment efforts that need to happen as well — but this is a key component of how we can make an impact."

Kheterpal adds that Precision Health improves the transparency of the data that health care providers have access to when they make a recommendation to a patient. "That's going to require some changes both on the part of providers who are giving that information and on the part of the patient or the health participant who's receiving that information," he says.

Addiction: A Brain Disease

A 2007 perspective article in The Lancet posed a question: "Opiate addiction: medical condition or moral failing?" In the medical community, the answer has been clear for a long time: Addiction is a brain disorder — a chronic but treatable medical condition that involves changes to circuits involved in reward, stress, and self-control, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). "Informed Americans no longer view addiction as a moral failing, and more and more policymakers are recognizing that punishment is an ineffective and inappropriate tool for addressing a person's drug problems," NIDA points out. "Treatment is what is needed."

It's helpful to view addiction through the same lens as other chronic conditions. "People often use the parallel of diabetes," Bohnert says. "We wouldn't say that a person with Type 2 diabetes doesn't want to get better just because they crave a piece of cake. In the same way, we shouldn't assume that someone with addiction doesn't want to get better because they crave the substance.

"I think the altered mental state of someone who is addicted allows us to dehumanize them," Bohnert says. "But they're still a person, one who needs help, who needs compassion."

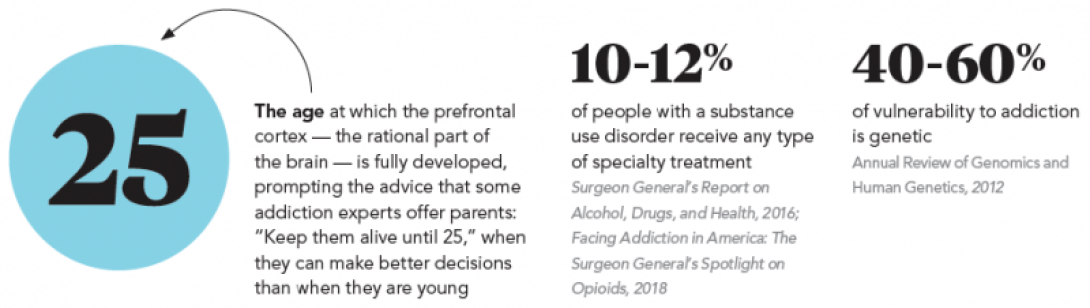

Scientists have learned a lot in recent years about what happens when someone takes an opioid: The brain's reward system feels an intense rush of dopamine — which is one of the brain's neurotransmitters, a chemical that carries information between neurons. The brain wants to repeat the euphoric feeling, and the person who used the opioids often tries again in an attempt to repeat that feeling. Regular drug use can lead to a reduction in the transmission of dopamine, ultimately leading users to take more drugs to avoid the associated negative feelings and emotions.

In his experience treating people who use drugs in the emergency room and in the psychiatric clinic, Christopher Blazes, M.D., assistant professor of emergency medicine and of psychiatry, has come to think of dopamine in a different way than conventional wisdom would dictate.

"What I've noticed from my practice is that people who do well in recovery are those who establish new connections and find new ways to feel contented, over and over and over again." —Christopher Blazes, M.D.

He sees it not as a pleasure molecule per se, but rather as something that helps you remember a pleasurable moment. It's a matchmaker, one that makes associations and links things by forming neural networks: "One patient said, 'I was polishing my shoes and wearing a blue shirt when I first used heroin, so every time I wear my blue shirt and polish my shoes, I want heroin.'"

Says Blazes, who also is an addiction psychiatrist in the U-M Addiction Treatment Services program: "What I've noticed from my practice is that people who do well in recovery are those who establish new connections and find new ways to feel contented, over and over and over again."

Understanding Children's Brains

What if we could predict which children are most likely to become addicted to opioids and other drugs? Could we create interventions specifically for them, in an effort to prevent them from starting to use the drugs in the first place?

That's one of the possible outcomes of a new national research study gathering data from 9- and 10-year-olds. Mary Heitzeg (Ph.D. 1999), associate professor of psychiatry and member of the U-M Addiction Center; and Robert Zucker, Ph.D., professor emeritus of psychiatry, are leading the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study at U-M, one of 21 institutions nationwide recruiting a total of more than 11,000 children to participate in the research.

While the study is not specific to opioid addiction, it is likely that it will inform a new understanding about how addictions develop. ABCD is analyzing brain development in a way that could shed light on how childhood experiences — everything from video games to social media to smoking — interact with each other and with a child's changing biology to affect brain development and social, behavioral, academic, health, and other outcomes.

"The work that I do looks at how we prevent people from actually becoming addicted. We know that rates of substance use, across all substances, are increasing throughout adolescence. They peak between the ages of about 18 to 21," Heitzeg says of the ABCD study as well as her other research. "How do we really get ahead of this? How do we understand who is going to be at risk prior to the point at which they start to use substances — prior to the age of 13?"

The ABCD study, currently underway, involves brain scans taken while children are completing tasks in order to observe which parts of their brain those tasks activate. Every six months, researchers will check in on the children through a phone call to see if there have been notable changes in behavior or mood. And the researchers will meet with the children annually over a 10-year period, which will allow them to gather a decade of neuroimaging data.

"The really interesting piece of this is that we know not all kids try drugs, and not all kids who try drugs continue to use drugs and go on to have a substance use disorder; we're interested in what differentiates those kids. Are there differences in reward-system functioning and prefrontal functioning early on?" Heitzeg says. "We are trying to understand a key question: What makes resilient kids? We want to catch kids prior to any significant substance use."

Moving Forward

Not since the HIV/AIDS epidemic has the U.S. faced "as devastating and lethal a health problem as the current crisis of opioid misuse and overdose and opioid use disorder," says a report, "Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic," published in 2017 by The National Academies Press.

Yet researchers from U-M and institutions around the world continue to make significant discoveries and advancements that could reverse the trend. They are also raising awareness of opioid use disorder and the highly addictive nature of this class of medications, and of the success of medication-based treatment.

Blazes, who has seen the fallout of the epidemic up close in his clinic office and the emergency room, maintains an optimistic point of view: "Addiction," he says, "need not be a life sentence."

Clare Duckworth, Kara Gavin, and Alex Piazza contributed to this report.

Pain Specialist: No Opioid Prescriptions in 10 Years

Despite a lack of evidence to support the use of opioids for chronic pain, they're still widely prescribed. People in the U.S., less than 5% of the global population, consume 80% of the world's opioids.

The director of the Michigan Medicine Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, Daniel Clauw (M.D. 1985), has received worldwide media attention for saying that he does not prescribe opioids for his chronic pain patients. Routine clinical practice underuses safer options for chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, interstitial cystitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, says Clauw, professor of anesthesiology, of internal medicine, of psychiatry, and member of the Division of Rheumatology.

"I haven't prescribed an opioid for chronic pain in at least a decade," Clauw says. "Narcotics don't work for most types of chronic pain, and overprescribing of narcotics in the United States has led to a serious public health problem with many deaths and overdoses. We need to modify how we approach individuals with chronic pain."

Clauw acknowledges opioids may be helpful for malignant pain and some cases of osteoarthritis and chronic lower back pain, if other pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies are not working. But he urges providers to exhaust all other options before prescribing an opioid. He says classes of medications like tricyclic drugs, gabapentinoids, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can be effective in treating chronic pain and are not always considered or used in individuals with chronic pain. Exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and a number of complementary and alternative therapies can also be effective for individuals with chronic pain, he adds. —Haley Otman

What About Marijuana? It's Complicated.

Slowly but surely, the stigma surrounding marijuana use is losing its grip in the U.S. As of 2018, 33 states and the District of Columbia have approved the medical use of cannabis, while 10 states have legalized marijuana for recreational use. Still, at the federal level, marijuana remains a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Substances Act, defined as a drug with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse (the same category as heroin, and a stricter category than oxycontin and fentanyl).

Researchers from the U-M Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center (CPFRC) published a study this year in Health Affairs that found the vast majority — 85.5% — of medical cannabis license holders in state registries indicated they were seeking treatment for conditions where cannabis has strong or conclusive evidence of therapeutic efficacy. Chronic pain accounted for 62.2% of all patient-reported qualifying conditions.

Lead author Kevin Boehnke, Ph.D., research investigator in the Department of Anesthesiology and the CPFRC, and his fellow researchers — including Daniel J. Clauw, M.D., professor of anesthesiology, of internal medicine, and of psychiatry; member of the Division of Rheumatology; and director of the CPFRC — examined the conditions for which people obtained medical cannabis licenses. Then, they investigated the strength of the evidence for these conditions using a 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on cannabis, which found conclusive or substantial evidence that chronic pain, nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy, and multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms were improved as a result of cannabis treatment. The new research provides support for legitimate evidence-based use of cannabis that is at direct odds with its current drug schedule status, notes Boehnke.

In a separate letter published in 2019 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Boehnke and Clauw addressed the minimal guidance that is available to physicians seeking to counsel patients about the use of cannabis. They note that while tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has known analgesic effects, it also causes most of the risks associated with cannabis, including intoxication, impairment, and addiction. While far less studied with chronic pain in humans, cannabidiol (CBD) is non-intoxicating, and evidence suggests it may have anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving effects.

Another 2019 Michigan Medicine study examined one of the effects of the increased use of cannabis to treat chronic pain. The study found that more than half of people who take medical cannabis for chronic pain say they've driven under the influence of cannabis within two hours of using it at least once in the last six months, says lead author Erin E. Bonar, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry in the U-M Addiction Center and a clinical psychologist at U-M Addiction Treatment Services.

"There is a low perceived risk about driving after using marijuana, but we want people to know that they should ideally wait several hours to operate a vehicle after using cannabis, regardless of whether it is for medical use or not," Bonar says. "The safest strategy is to not drive at all on the day you used marijuana." There is no agreed-upon, scientifically established limit for the amount of marijuana a person could have and still be considered safe to drive, and in most jurisdictions evidence of impairment or a positive blood test can result in legal penalties for impaired driving. —Kelly Malcom and Stephanie Abraham

Five Signs That Your Loved One May Be Struggling

Katie Donovan can see the signs more clearly now, with the benefit of hindsight. Her daughter, Brittany, was a straight-A student and a high school athlete. But during her senior year, Brittany "started not wanting to be around the family as much. She had an attitude. Then she started waking up with the flu a lot. She was vomiting and very lethargic," recalls Donovan. "You make these things up in your head and are not really seeing the true signs." Brittany would later tell her mother that she was addicted to heroin.

Donovan, of Macomb Township, Michigan, is now a family training coach and interventionist, and the author of the blog A Mother's Addiction Journey. She wishes she had known the signs earlier, and that she could have seen Brittany's addiction in its infancy — before her multiple overdoses and suicide attempts. "I saw a switch, but it was gradual." Her message to parents and others: Trust your gut.

Edward Jouney, D.O. (Residency 2007, Fellowship 2011), clinical instructor of psychiatry and an addiction psychiatrist, says people with drug addiction can present in varying ways, and that some people are able to conceal the problem from loved ones. Often, though, there are signs:

1. Personality changes, including being easily agitated and experiencing dramatic mood swings

2. Large amounts of money going missing

3. Having difficulty being honest with loved ones and health care providers

4. Decline in work performance

5. Opiate use in high doses may result in pinpoint pupils, an altered level of consciousness, and an inability to arouse in the more severe cases (it should be noted, Jouney says, that many patients with chronic opioid use may not exhibit any significant clinical signs or symptoms)

Why Today's Drugs Are More Lethal Than Ever

Illegal opioids — such as heroin and the synthetic drug fentanyl — have increased not only in supply but in potency through the years. Many people who began their addictions with a prescription opioid ultimately transition to illegal drugs, which can include heroin that has been cut with fentanyl for increased potency. Often called "manufactured death" in law enforcement circles, fentanyl is now the leading cause of opioid overdose deaths and is 30-50 times more potent than heroin.

"A tiny amount of fentanyl is equivalent to a large amount of heroin," says Christopher Blazes, M.D., assistant professor of emergency medicine and of psychiatry, and an addiction psychiatrist at the U-M Addiction Treatment Services program. There are also hundreds of analogues of fentanyl created by different chemists. "Most routine drug screens don't even test for fentanyl. Even the ones that do will miss a significant portion of these new synthetic fentanyl analogues."

Clinicians are often left in the dark, not knowing what caused the overdose and not able to predict how emergency interventions will respond, Blazes says. "These fentanyl analogues are so variable and so unpredictable. Many of our classic, evidence-based treatments either don't work, or can now cause dangerous side effects."

Seeking Help: Not Every Treatment Center is the Same

There are several levels of care in addiction treatment, and a licensed health care provider who has experience treating substance use disorders should determine which level is appropriate for each patient, says Edward Jouney, D.O. (Residency 2007, Fellowship 2011), clinical instructor of psychiatry and an addiction psychiatrist in the U-M Addiction Treatment Services program.

Basic outpatient care is usually reserved for individuals who are relatively stable, and who are in need of supportive services, Jouney says. Medical detoxification, which usually lasts five to 10 days, is carried out at an inpatient unit of a substance use treatment facility. This is reserved for individuals typically utilizing alcohol, sedatives, and/or opiates, who necessitate treatment in a medically supervised environment, as they are gradually withdrawn from the substance. Long-term residential care, Jouney says, is a treatment program extending for 30 days or longer, usually in a therapeutic residential setting.

The most important thing to look for is a facility that offers medication-assisted treatment (MAT), says Amy Bohnert, Ph.D., associate professor of psychiatry. She adds that she would look for a treatment facility that is affiliated with a major medical center. If that isn't available, she recommends treatment at a facility that has doctors and nurses on site at all times.

Vivek Murthy, M.D., issued a Surgeon General's Report on Addiction in 2016, when he held the office. The report was unequivocal on this issue: "The research clearly demonstrates that MAT leads to better treatment outcomes compared to behavioral treatment alone. Moreover, withholding medications greatly increases the risk of relapse to illicit opioid use and overdose death. Decades of research have shown that the benefits of MAT greatly outweigh the risks of diversion." Some see medication-assisted treatment as substituting one substance for another and promote abstinence-only, Murthy says, but "this is not backed by science."

Katie Donovan, who lives in Macomb Township, Michigan, helped her daughter Brittany get into a rehab facility at age 17 and many more in subsequent years. Donovan is now a family training coach and interventionist, and the author of the blog A Mother's Addiction Journey. In the beginning, "I assumed every treatment facility would be a great facility," she says. Now she knows what to look for — and she encourages readers of her blog to do the same. "One of the things I guide families to is making sure it's a strong, clinically appropriate program." She looks for a counselor-to-patient ratio of 1:6 as opposed to, say, 1:15. And she looks for facilities that are affiliated with medical centers.