Emily Haller, M.S., R.D.N., the senior dietitian for GI Nutrition Services at Michigan Medicine, is sharing the best news of the night with the attendees of a low-FODMAP cooking class. Several students have pointed out — woefully — that they thought garlic wasn't allowed on the diet, which has shown to be effective in improving the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

True, says Haller, garlic is an exceptionally concentrated source of fructans, a no-no on a low-FODMAP diet elimination phase. But garlic-infused olive oil is allowed because the fructans in garlic are not oil soluble, she explains, so you get the garlic flavor without the FODMAP (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides, and polyols — in other words, short-chain carbohydrates such as fructans that are resistant to disgestion). That distinction paves the way for Haller to be the bearer of good garlic as she showcases a collection of FODY Food Co. garlic-infused olive oil bottles.

In Oprah fashion, Haller announces, "You get a bottle, and you get a bottle, and you get a bottle! Everyone is going home with a bottle."

One student practically squeals in delight. She can cook with garlic again, and her diet is suddenly about the foods she can eat rather than the ones she can't. Students praise the flavor of the quinoa, salmon, and red pepper hummus dishes they are trying tonight and revel in their newfound knowledge that the diet doesn't have to be bland or limited. One student asks if she can marry Haller so the dietitian can make homemade almond milk for her. And they are all beginning to see a world in which a diet that helps their medical conditions can also be defined by variety rather than deprivation.

The Emergence of Culinary Medicine

The class is part of a new program at Michigan Medicine in which food is a centerpiece, and scientific research is a backdrop. The Culinary Medicine program is part of a growing field of medicine that explores the links between food and health, using evidence-based dietary standards in combination with medications.

Culinary Medicine at Michigan Medicine is led by William Chey, M.D. (Fellowship 1993), the Timothy T. Nostrant, M.D., Collegiate Professor of Gastroenterology, and professor of internal medicine and of nutritional sciences. The goal is to set patients on a path in which they understand the way diet affects their digestive systems and how it can help improve their overall health. Weaving nutritional interventions together with medicine, Chey says, has proven beneficial for many of his patients.

It has been longstanding medical practice, of course, for gastroenterologists and other specialists to discuss diet and nutrition with their patients. But Chey and colleagues have taken it to a new level by integrating scientifically sound food research and cooking classes, as well as one-on-one sessions between patients and registered dietitians, and patients and clinical psychologists.

The genesis of the program was about 12 years ago, when Chey and his colleagues started a GI nutrition program, complete with a dedicated GI nutritionist. "At the time, it was a maverick move," says Chey, also the director of the GI Physiology Laboratory, director of the Digestive Disorders Nutrition & Lifestyle Program, and medical director of the Michigan Bowel Control Program. In the years that followed, other GI departments around the country have caught on, and Michigan Medicine has evolved further.

Today's Culinary Medicine program at Michigan Medicine is among the leaders in the field nationwide. It includes three GI dietitians and two psychologists who focus specifically on digestive-health issues. For Chey, the multifaceted approach is key to the program's success; everyone is treated as an equal part of the team, rather than it being exclusively physician-centric. "Care of digestive disorders in 2020 is a team sport," Chey says.

The program includes the new U-M Food for Life Kitchen, which is co-led by Chey and Erica Owen, manager of U-M's MHealthy Nutrition and Weight Management program. Classes are offered at the kitchen, which is at the East Ann Arbor Health and Geriatrics Center on Plymouth Road, focusing on diseases — such as the IBS/ low-FODMAP class referenced earlier. Patients and anyone in the community can sign up for the $30 classes, all of which a dietitian teaches with a chef from MHealthy.

The program's goal is to find the right balance for individual patients. Chey believes that balance is best found when all parts of the team work together. And while he is a proponent of dietary changes and mental health support in the quest for digestive equilibrium, that doesn't mean he is against medications. "I'm a huge fan of medications in the right patients," Chey says. "But I want my patients and other physicians to understand that medications aren't the only solution."

It's also not enough for a health care provider to give a patient a printout about how the Mediterranean Diet can help people with fatty liver disease. "I think most physicians right now are trying to manage diet by giving patients a sheet of paper with a list of foods to eliminate, and that's simply inadequate," Chey says. "Diets are definitely more comprehensive and complicated than can be conveyed with a sheet of paper — even potentially dangerous if not administered in a medically responsible way." (See "Can a Diet Be Too Healthy?")

Teaching the next generation of physicians about the importance of understanding diet and nutrition is the goal behind a Medical School elective that has been offered in recent years. The culinary medicine class teaches students about the connection between nutrition and medicine so they can provide sound advice to patients in the future.

Without question, they will need that training; GI disorders such as acid reflux, IBS, fatty liver disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis are on the rise, as are cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Many factors led to this rise, but Chey says the main culprit is the adoption of the Western diet. "It contains a lot of calories, a lot of refined sugars, processed foods, and fat while being deficient in fruits and vegetables.

"Patients need research now. They need treatments now. They need ideas about how to cook foods that taste good and don't aggravate their symptoms," Chey says. "They need holistic, high-quality care, and that's what we are providing."

Dinner Is Served

On an evening in fall 2019, the Food for Life Kitchen opens its doors to local physicians. They are here to learn from Chey and others on the team about how to teach patients the importance of sound nutrition. The physicians in the room are treated to a dinner prepared in the Food for Life Kitchen, including ginger-sesame salmon, miso and chili tofu skewers, sweet and sour slaw, and a soba noodle salad.

They are also served information. Chey begins by saying that all physicians need to have a better understanding of diet. Chey shares a headline from JAMA with the diners: "Ignorance of nutrition is no longer defensible."

Indeed, he says, all general practitioners and gastroenterologists need to be much more fluent in the language of diet. For example, he says, "everyone in this room knows IBS is one of the most common conditions we deal with," and the second most common cause of work absence, after the common cold. And a strikingly large number of IBS patients — some 50 to 60% — get better with structured dietary interventions.

They don't have to do it all alone, though. Chey quotes from the JAMA editorial: "Physicians should work with registered dietitians. Physicians do not need to do their own diet counseling, any more than they need to perform their own radiographs or laboratory assays. But they must recognize the role nutrition plays in disease, communicate it clearly to the patient, and refer the patient appropriately."

Shanti Eswaran (M.D. 2002, Residency 2005), associate professor of internal medicine, emphasizes the importance of good digestive health during her presentation to the physicians. "A good reliable set of bowels," she quotes the humorist Josh Billings, "is worth more to a man than any quantity of brains."

The Mind-Gut Connection

If food and medications are two of the legs of this treatment tripod, behavioral health is the third. The physicians in the Culinary Medicine program work with a behavioral therapy care team made up of two clinical psychologists who specialize in evidence-based treatment of GI conditions.

Megan Riehl, Psy.D., who helps to lead the program and Christina Jagielski, Ph.D., MPH, teach patients several relaxation strategies to help them cope. Those methods include deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and gut-directed hypnosis. Most of the patients in the clinic have IBS or another functional bowel disorder.

"Being able to have a GI psychologist added to the treatment team is very often the thing that people who have been struggling with GI symptoms say they've been looking for," Riehl says. "I have the unique role to work with patients and really help manage a GI condition." In addition to the emphasis on behavioral health within the Division of Gastroenterology, the U-M Medical School also recognizes the need for the specialty; it offers one of the only post-doctoral programs for GI psychology in the U.S.

Riehl often uses hypnosis with patients. She suggests that they pay less attention to the uncomfortable pains they experience in their digestive tract to reduce the perception of pain and to relinquish the control that GI stress has on their symptoms. The practice has been so effective that she routinely uses gut-directed hypnotherapy with patients for whom other medical treatments have failed.

Another therapy involves arming patients with cognitive behavioral therapy concepts such as constructive self-talk and decatastrophizing. "This teaches them to observe themselves having those unhelpful thoughts during times of discomfort or stress and realize that we can talk back to the thoughts and find alternative ways of thinking," Riehl says.

Wood feels a sense of freedom. She can eat breakfast without fear of a debilitating pain that will keep her from her patients.

She also emphasizes the value of identifying a worst-case scenario (a bathroom accident, for instance) and having an action plan ready in case it occurs. Riehl reminds them it may be embarrassing, but it won't be the end of the world.

As with the dietary interventions in Culinary Medicine and the Division of Gastroenterology, behavioral therapy is personalized for each patient. The results vary from person to person, but the successes have been widespread.

"This work is so gratifying because often in such a short period, anywhere from three to seven sessions, patients have such a dramatic improvement on symptoms they've sometimes had for their entire life," Riehl says.

"100% Better"

For years, Sarah Wood had tried to eat right: lots of fruits and vegetables, riced cauliflower in place of regular rice, protein bars before her workouts to help her build muscle. But she spent much of her adult life with a sometimes debilitating pain in the lower-right quadrant of her abdomen. The pain initially was helped by endometriosis surgery, but it still returned too often for her to live a normal life. Eventually, she learned that the pain likely was caused by scar tissue from the endometriosis that adhered to her intestines. When she became bloated, her digestive tract would tug on the scar tissue, causing the pain flare-ups.

She tried pain medications, but none of them worked; she also didn't want to be on pain medications the rest of her life. A physician suggested surgery, but Wood persisted in thinking that a non-surgical approach could work. After too many times of curling up on the floor at work in pain, of not eating breakfast for fear of triggering the pain while she was working, of eliminating and reintroducing foods in her diet to no avail — Wood knew she needed to try something else.

Her OB/GYN sent her to Haller, a GI dietitian at Michigan Medicine. Haller learned about Wood's experiences and her own attempts at resolving the problem. She suggested a low-FODMAP diet with an elimination of high-FODMAP foods for a month, followed by a slow reintroduction of one FODMAP group at a time. "GI conditions can be so disruptive. Our patients tend to be very motivated to find a solution," Haller says.

Wood, D.O., who is a clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at Michigan Medicine, followed Haller's guidelines — even the ones that seemed counterintuitive. "I had no lactose, no wheat, and certain fruits and vegetables weren't allowed. I learned that the guidelines aren't intuitive. For instance, I would've never singled out pistachios and cashews as the only nuts you couldn't have. I remember one day when my father-in-law was visiting, and I was making myself bacon and eggs. He said, 'What kind of diet are you on?'" she recalls with a laugh.

Because of such complexities and a need for personalization in patients' diets, outcomes are much better when people work with a registered dietitian than when they try to navigate a new diet on their own, Haller says.

The dietary changes were challenging, but for Wood, this was a much better option than trying to resolve the problem with surgery. "It was difficult, but I was extremely motivated," she says.

A month later, she was able to return to Haller with good news. "I was able to tell her I felt 100% better," Wood says.

Next came the reintroduction phase. Wood started with protein bars; within three days, she was doubled over in pain. Next she tried sugarless gum and mints, with the same results. Other foods have caused some issues, but nothing as clear as the protein bars and the sugar alcohols in the gum and mints. She has cut out those foods entirely, and reduced her intake of some other triggers.

Wood feels a sense of freedom. She can eat breakfast without fear of a debilitating pain that will keep her from her patients. She no longer carries pain medications and a heating pad in her work bag. She does not anticipate needing surgery. "It's been a really long journey," Wood says, "but I feel very grateful that it turned out how it has. This is the best I've felt in many years."

Can a Diet Be Too Healthy?

"If you told me that I could only eat this one food for the rest of my life and my symptoms would be resolved, I would do it." That's a statement that Megan Riehl, Psy.D., assistant professor of internal medicine at U-M, often hears from GI patients. For Riehl, it also indicates how vulnerable GI patients are to disordered eating. People in digestive pain frequently turn to the internet, where they may run into info about the low-FODMAP diet as well as fad diets and anecdotal diet advice.

"Sometimes they unintentionally follow diets they don't need to be on," Riehl says. If a person's diet becomes very restrictive and they have increasing anxiety about the health of their food choices, they may have orthorexia, a condition marked by obsession with healthy eating that can lead to malnutrition, crippling anxiety, and strained relationships. "The thing that I'm most concerned about is that they're getting evidence-based nutritional guidance," says Riehl, who doesn't want patients who need specialized diets to go it alone without help from a dietitian.

Orthorexia is not recognized in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. According to the National Eating Disorders Association, this is mainly due to disagreement among experts about whether it is a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder, a feature of anorexia, or an eating disorder in its own right. But it is a real problem, especially for GI patients. "We need to do more work to assess how people are eating and their thoughts around food," Riehl says. Someone can look healthy, but they may only be eating a small subset of foods or following rigid rules that impact other areas of their life.

If Riehl discovers that a patient is overly concerned with healthy eating, she begins by having a nonjudgmental conversation with the patient about their diet and what orthorexia is. Then she recommends a multidisciplinary treatment plan with health care providers to manage the patient's food anxiety as well as their GI complaints. "I've noticed an increase [in the incidence of orthorexia], but we're also getting better at training for it, too." —KW

Go with Your Gut

Paleo, Whole30, ketogenic, Mediterranean, macrobiotic, plant-based, vegan, raw, gluten-free, sugar-free, low-fat, low-carb, low-FODMAP, high-protein. The options for a "healthy" diet are endless. And contradictory recommendations from the internet, commercials, colleagues, friends, and news stories can be overwhelming.

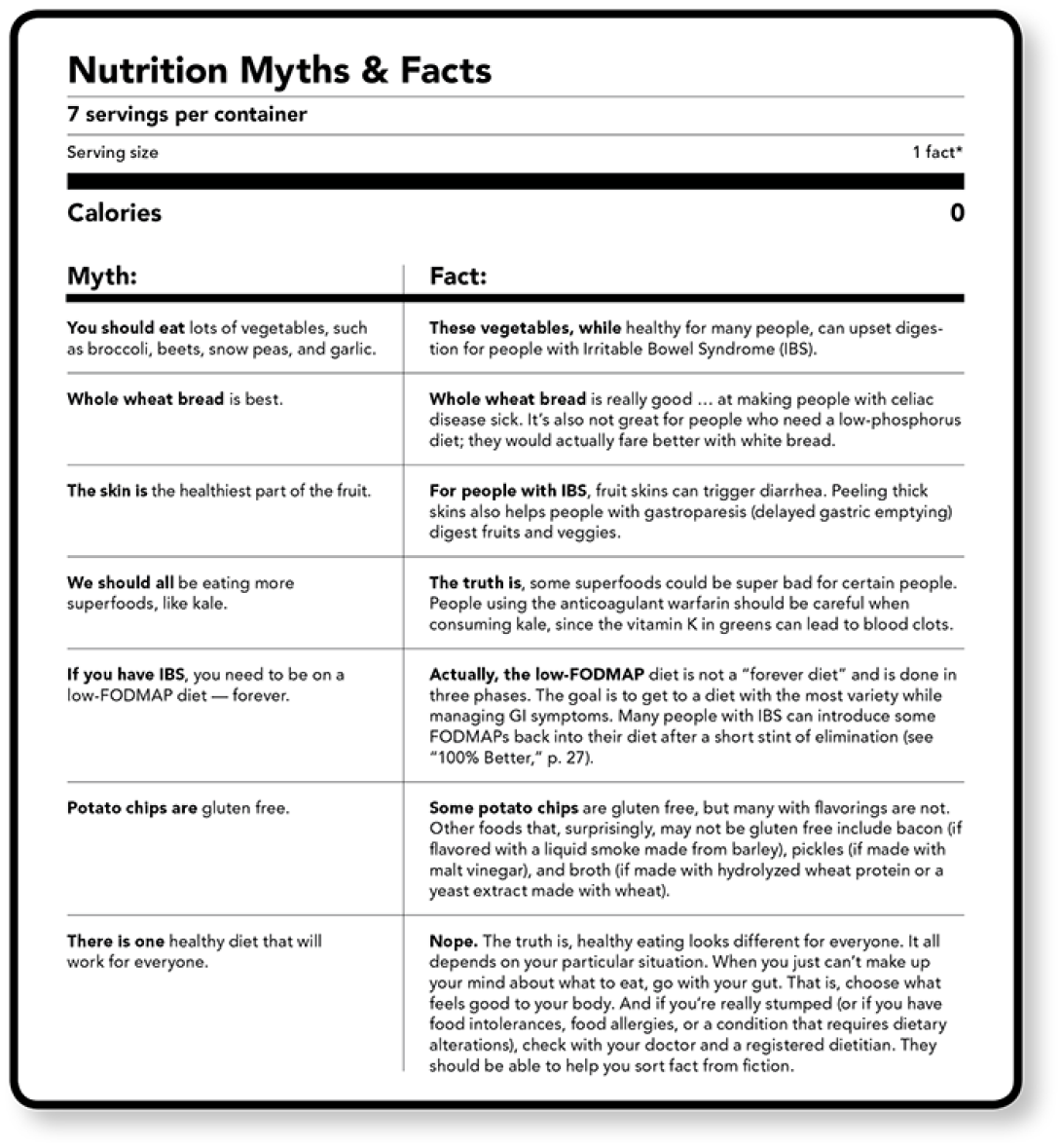

The table below is not meant to help you understand the nuances of specialized diets. Instead, it's meant to call into question common food "facts" that many of us (I'm looking at you, internet) assume to be true. If you consume sweeping judgments about food with a side of skepticism, you'll be in a better position to make food choices without obsessing over health concerns.

Easy to Swallow

BY KATIE WHITNEY

For patients who have dysphagia, a condition in which they have difficulty swallowing, foods that are too thin can be just as dangerous as those that are too thick. Because of the intricacies of feeding patients who have the disorder, Michigan Medicine's Patient Food & Nutrition Services (PFANS) in 2019 became an early adopter of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI). Before IDDSI, food providers relied on vague standards, like comparing a beverage's thickness to that of honey. Now they have a rigorous, eight-level scale.

For people with dysphagia, solid foods pose a choking hazard and thin liquids can lead to aspiration. To strike the right balance, PFANS staff members used the "Fork Test" to evaluate thick foods and purees by assessing how they pass through the tines of a fork and the "Syringe Test" to measure the time it takes for a liquid to pass through a syringe. Patients on the most restrictive dysphagia diet can now choose from menu items such as cheesy potato bisque, shaped pureed pancake with syrup, and "Butter Pecan Magic Cup."

The IDDSI implementation is only one of several initiatives PFANS has undertaken to offer patients the best possible dining experience. PFANS director Kit Werner, Ph.D., M.S., R.D.N., has met with rabbis and Muslim spiritual leaders to gain a better understanding of kosher and halal diets. For patients who need to pump breast milk, C.S. Mott Children's and Von Voigtlander Women's hospitals have the first aseptic formula and breast milk preparation room in a pediatric hospital nationwide. PFANS has even thought about those who aren't eating: If a patient hasn't ordered a meal in a while, PFANS can send a dietetic assistant to their room to order for them, "so they don't have that burden of having to use the phone," says Werner.

Information from the U-M Colleagues in Care publication was used in this article.