Less than 1 in 5 adults rate quality of diet, safety of communities, and exercise and fitness as better for kids today than their predecessors, a U-M-led study finds.

11:00 AM

Author |

Ask adults of all ages if today's children are healthier than children of their own generation.

Too often, the answer is "no."

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

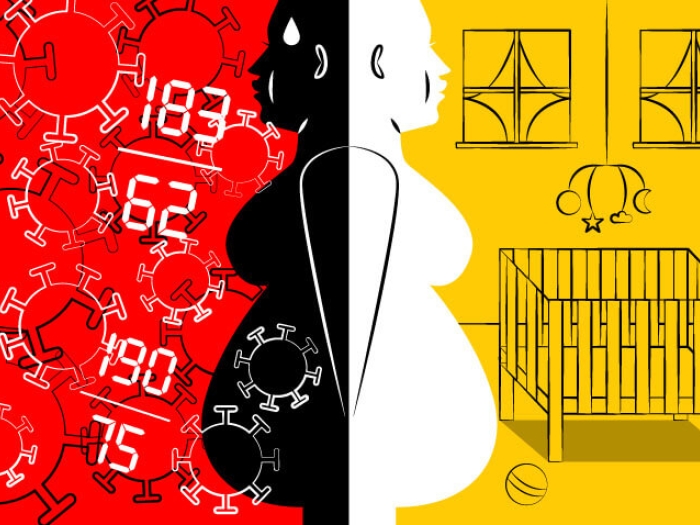

Less than one-third of adults believe that kids are physically healthier today compared to kids in their own childhoods, according to a new study in the journal Academic Pediatrics. And fewer than 25 percent think the mental health status of children is better now.

"Our findings clash with the American dream of expecting that the quality of life will continue getting better for future generations," says lead author Gary Freed, M.D., M.P.H., a pediatrician at University of Michigan's C.S. Mott Children's Hospital and a member of U-M's Child Health Evaluation and Research Center.

"We have made remarkable gains in preventing communicable diseases, advancing technology and developing cures that have significantly reduced children's illness and death over the last century," Freed says.

"However, we are clearly falling short in addressing challenges affecting children's health today, including mental health, bullying, safety and obesity."

The study, led by Mott and the Children's Hospital Association, used 2016 data from a C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health. The survey encompassed a nationally representative household sample of 1,330 respondents.

Barriers and beliefs

Researchers evaluated adult attitudes toward six factors that influence the health and well-being of children.

Of these, only two factors were believed to be better for children today by more than a quarter of poll respondents: quality of education (36 percent said it was better when they were growing up) and quality of health care (39 percent).

But a smaller minority of respondents believed that emotional support from families (23 percent), exercise and fitness (18 percent), quality of diet (17 percent) and safety of communities (14 percent) was now better for children.

SEE ALSO: Why Screening for Social Determinants of Health Helps Doctors Provide Better Care

Only 15 percent of poll respondents said the chances for a child to grow up with good mental health in the future are better now than when they were growing up.

"Mental health issues are rapidly emerging as a dominant factor in the well-being of children and a chief concern of parents today," Freed says.

The negative perception was most prevalent among the youngest contemporary generations –with only 10 percent of Generation Xers and 6 percent of millennials believing that kids today will grow up to have good mental health in the future.

This, Freed says, could be because impressions of health challenges fade with time and younger generations may not have appreciated such dramatic positive changes in health for children in their lifetimes. On the other hand, some believe childhood health conditions have indeed worsened due to emerging concerns with such issues as obesity and mental health problems, he says.

Impetus for change

Regardless of the reason, such divides underscore the need for policymakers and health care professionals to consider the needs of young people as much as the issues facing their elders.

"These findings should raise an alarm," Freed says. "Although demographic changes require continued focus on our aging population, we must equally recognize the importance of advancing a healthy future for our nation's children.

"We need to work hard to make sure that children of today have the potential to be the healthiest generation America has ever seen."

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!