A patient with lupus weighs in on the COVID drug debate.

4:49 PM

Author |

Editor's note: Information on the COVID-19 crisis is constantly changing. For the latest numbers and updates, keep checking the CDC's website. For the most up-to-date information from Michigan Medicine, visit the hospital's Coronavirus (COVID-19) webpage.

Interested in a COVID-19 clinical trial? Health research is critical to ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Our researchers are hard at work to find vaccines and other ways to potentially prevent and treat the disease and need your help. Sign up to be considered for a clinical trial at Michigan Medicine.

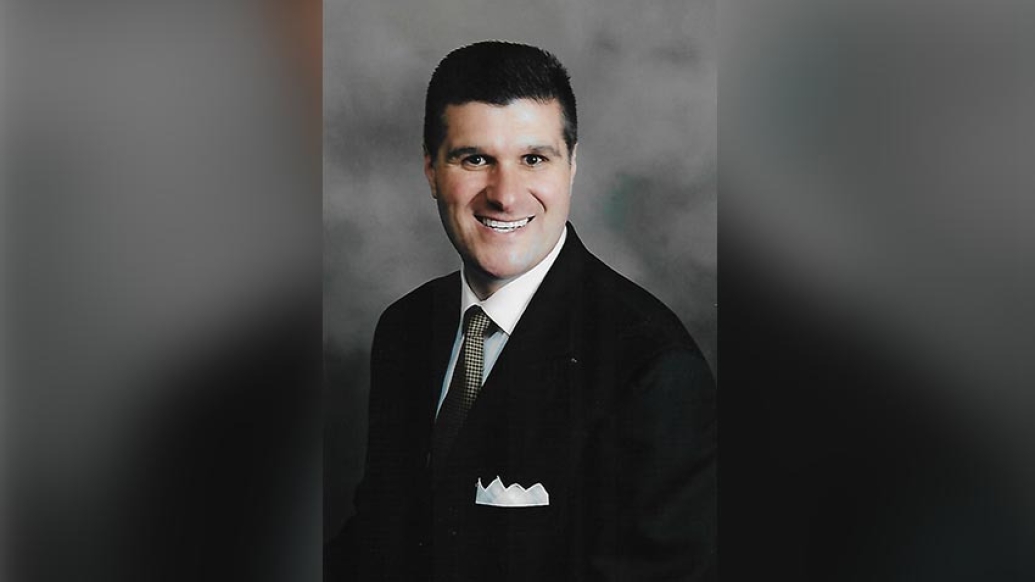

Brian Joseph is no stranger to death. But life as a funeral director and a person living with lupus during the COVID-19 pandemic has given him pause. Mortuary services are considered critical services exempt from the shelter-in-place declarations designed to slow the spread of the disease. And recently the calls to his five funeral home locations in southeast Michigan have increased.

"We're in a hotspot in Detroit," says Joseph. "We have four immediate burials today and three of them were COVID patients." As a result, the homes have taken measures to protect both families and staff and to offer care to the best of their ability in an era of social distancing.

The fact that some of those victims had the same underlying condition he has is not lost on him. "I've seen lupus patients that are dying. On the death certificate it says cause of death: respiratory failure or COVID-19 and other significant factors: lupus or diabetes or SLE," he says. "Does that not force me to step back and look? This is where my faith comes in. It tells me strongly to inhale and do everything that the scientists say."

One of the medications Joseph takes to manage his condition is called Plaquenil and was recently touted as a promising drug against COVID-19 by President Trump.

With a keen eye on the developments in China, Joseph's physician, Michigan Medicine's J. Michelle Kahlenberg, M.D., Ph.D. of the department of internal medicine in the division of rheumatology, had advised him to fill his prescription just before that pronouncement was made. His current 90-day supply should take him into May, he says. After that, "I'm going to be saying to myself, ok, who has it, who can I call, where do I have to go to get it."

From diagnosis to drug

It took almost eight years for Joseph to get a diagnosis and treatment plan for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Beginning in 2005, he started having various, unexplainable symptoms, including rashes, debilitating joint pain, a pulmonary embolism and pericarditis. In 2012, a connection with Kahlenberg finally turned his life around.

"She laid out this whole map and said 'when you were in the hospital this time and this time, when they were treating you for a pulmonary embolism, each of these blood tests… there's links to systemic lupus," recounts Joseph. "She put a treatment regimen together and said immediately we're going to start this drug Plaquenil. It's a malaria drug."

Hydroxycholoroquine (the generic form of Plaquenil) was developed for use as an anti-malarial drug in 1955. Anti-malarials were discovered shortly before World War II and their widespread use led to the accidental discovery of their effectiveness against rheumatic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

"In general, we think of hydroxycholoroquine as a way to turn down the immune response to stimulus," says Kahlenberg. This is helpful for those with autoimmune disorders, whose innate immune systems overreact to perceived threats, she explains.

For people with lupus, hydroxycholoroquine is considered first line therapy. Among its many documented benefits for these patients, Kahlenberg notes that it increases life expectancy and helps mitigate side effects of chronic steroids in addition to lowering disease activity. "It's considered standard of care and every lupus patient should be on it unless they have a reason not to be, such as an allergy or they cannot tolerate it."

The COVID connection

That fact and the fact that it's now being investigated as a treatment for COVID is leading to an intense debate among rheumatologists.

"The data we have so far for the efficacy of Plaquenil for treating COVID is not great," says Kahlenberg. "The trials are not randomized controlled trials, they have design flaws and even though they do show some benefit, it's hard to know how much because there's no placebo controlled comparator group."

Researchers around the world and at U-M are currently ramping up gold standard randomized controlled trials of hydroxychloroquine in an effort to get some fast answers. She notes that Plaquenil has been shown to stop the growth of COVID in in vitro studies of cells but it also showed similar effects against various other viruses, including influenza, SARS, hepatitis C and HIV. However, every time it's been looked at in a controlled fashion, she says, so far, it hasn't panned out.

In fact, "there have been randomized controlled trials looking at the benefits of Plaquenil in influenza and those showed that patients may actually do worse." Until the risk-benefit ratio is supported by data, Kahlenberg says use in low risk outpatients doesn't make sense.

For high risk patients with no other options, the decision becomes trickier, she says. "Right now, we don't have anything else and people are desperate to offer some hope."

For now, Joseph is hoping he doesn't have to deal with the ill effects of a worldwide shortage of the drug he relies on. "This drug works for lupus patients. If it works for a COVID patient, God bless 'em, that's great," he says. "But if doctors are just prescribing them to whomever, that is immoral, unethical and fringes on criminal."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!