A study in fruit flies reveals the dance of key proteins behind circadian rhythms.

5:00 AM

Author |

Almost every living thing on Earth—from bacteria to plants to people—have a circadian rhythm, the biological clock that controls both physiology and behavior of organisms over a 24-hour period.

This internal timekeeping has been the subject of intense study for decades (the discovery of the genes that drive it led to the Nobel Prize in 2017), yet just how circadian rhythms work within living cells has not been understood until recently.

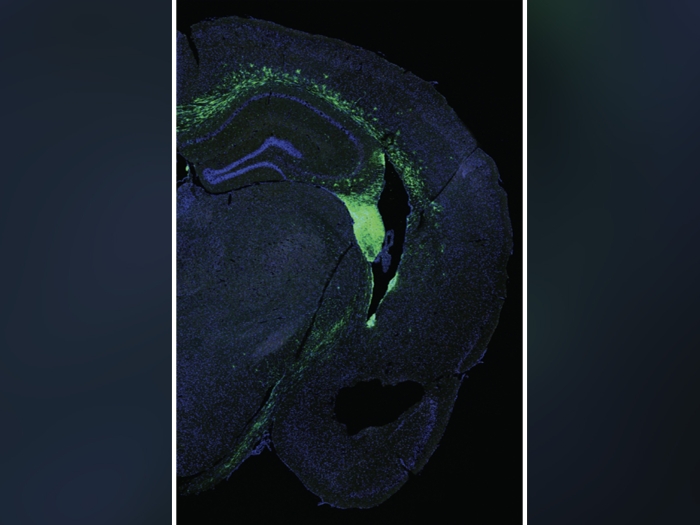

Using the relatively simple clocks found in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), University of Michigan researchers Yangbo Xiao, Ph.D., Ye Yuan, Ph.D., Swathi Yadlapalli, Ph.D. and their colleagues reveal that the subcellular location of clock proteins and genes fluctuates with the daily passage of time, indicating that spatial information is translated into time-related signals.

"We can now visualize these proteins within Drosophila brains while the clocks are ticking," said Yadlapalli, an assistant professor with the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology at Michigan Medicine.

The internal clock within a fruit fly and a person is generated by the rhythm of the expression of certain genes in response to environmental cues, like light. Some genes are more expressed during the day, while others are more expressed at night.

One of the most well-known processes controlled by the circadian rhythm is the sleep-wake cycle. This cycle is due in part to the production of the hormone melatonin, which fluctuates and is highest in the evening, causing drowsiness.

Several other bodily processes fluctuate over the 24-hour period, controlled by RNA expression that rises and falls over the 24-hour day. Clocks in all eukaryotes, organisms whose cells carry DNA inside an enveloped nucleus, are based on a simple negative feedback loop.

Genes are being moved to the edges of the nucleus within our cells then back again, essentially every 12 hours, every single day— throughout the life of the organism.Swathi Yadlapalli, Ph.D.

"Your cells are making key clock proteins and once you have high enough levels, those proteins enter the nucleus and stop their own mRNA production," explained Yadlapalli. The fruit fly clock is generated by four proteins called CLOCK, CYCLE, PERIOD and TIMELESS—which generate this feedback loop and control the expression of several clock-regulated genes. Using CRISPR to tag a clock gene called per, which codes for PERIOD, the researchers used a high-resolution microscope to observe its oscillations over 24 hours.

Her team discovered that PERIOD is surprisingly organized, not randomly distributed within a cell. The proteins produce foci, discrete spheres that are positioned around the edges of the nucleus, called the nuclear envelope, during the repression phase—when genes are not being expressed.

"Genes are being moved to the edges of the nucleus within our cells then back again, essentially every 12 hours, every single day— throughout the life of the organism," Yadlapalli said. This movement regulates the circadian rhythm.

The team further observed that flies without a nuclear envelope exhibited abnormal behavior in response to light and dark.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"If you disrupt this process in these 150 neurons in fly brains, it affects the sleep/wake cycle of the flies," said Yadlapalli.

This study provides fundamental insights into how circadian clocks function at the subcellular level. Says Yadlapalli, "If the clocks are disrupted, which happens in old age and with some mutations, that can lead to many disorders, like sleep and metabolic disorders and even cancer, as clocks control when cells decide to divide."

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

Paper cited: "Clock proteins regulate spatiotemporal organization of clock genes to control circadian rhythms," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2019756118

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!