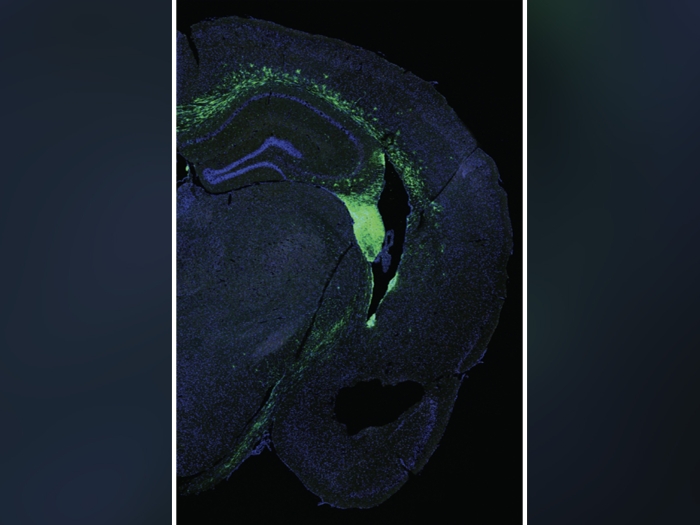

An atlas of neuronal circuits could help predict targets for medications to control appetite.

5:00 AM

Author |

Every meal you sit down to makes an impression, with foods filed away as something delicious to be sought out again, or to be avoided in disgust if we associate the flavor with gut malaise, colloquially known as a stomach ache.

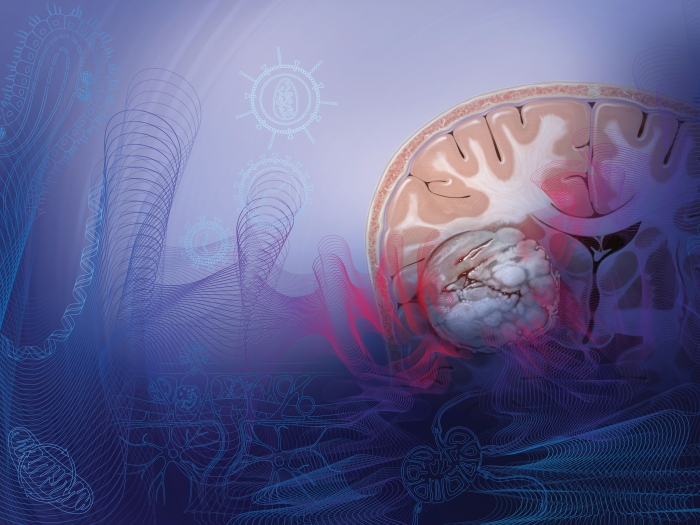

How this decision is made turns out to be so fundamental to our wellbeing—determining what foods to seek and avoid—that the signals are coordinated within the most primitive parts of our brains, the brain stem or hindbrain. This brain region also helps us decide when we are "full" and should stop eating.

To date, scientists interested in how and why people gain weight and the diseases that can result from overeating and obesity have focused on a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, following discoveries of two intertwined systems that play important roles in controlling energy balance, the leptin and melanocortin systems.

A paper in the journal Nature Metabolism looks outside this brain region and reviews the various brain pathways that meet in the brain stem to control feeding behavior, using a technique that offers an unbiased look at the neurons involved.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

"Everything the hypothalamus does ends up converging in the brainstem. The brain stem is super important in the control of feeding because it takes all sorts of information from your gut, including whether the stomach is distended and whether nutrients have been ingested, and integrates this with information from the hypothalamus about nutritional needs before passing it all on to the rhythmic pattern generators that control food intake," said Martin Myers, Jr., M.D., Ph.D., professor of internal medicine and Molecular & Integrative Physiology and director of the Elizabeth Weiser Caswell Diabetes Institute.

The recent review builds on recent findings in mice from the Myers lab that revealed the existence of two different food intake-suppressing brain stem circuits- one that causes nausea and disgust, and one that does not, as well as from collaborations with colleague Tune Pers, Ph.D., of the University of Copenhagen. Pers and his group used single cell mapping of brain cells within the dorsal vagal complex, a region in the brain stem that mediates a host of unconscious processes, including feelings of satiety (or sickness) after eating.

The new review paper, from first author Wenwen Cheng, Ph.D., Myers, Pers, and their colleagues, integrates these findings with other recent discoveries to build a new model of brainstem neuronal circuits and how they control food intake and nausea.

"Taking all of this information together allows us to predict which set of neurons control this or that function," said Myers.

He notes that many of these cell populations are targets for new and effective anti-obesity drugs— for example, a class of drugs for diabetes called GLP1 receptor agonists that can lower blood sugar and help you eat less.

"There is a population of GLP1 neurons in the brain stem which, if you turn them on, will stop food intake but cause violent illness, but there may be another population of neurons that stops eating without making you feel badly."

Having a detailed map of these neurons and understanding the effects of modifying these cell targets, Myers explains, can assist in making drugs with fewer negative side effects.

Paper cited: "Hindbrain circuits in the control of eating behaviour and energy balance," Nature Metabolism. DOI: 10.1038/s42255-022-00606-9

Live your healthiest life: Get tips from top experts weekly. Subscribe to the Michigan Health blog newsletter

Headlines from the frontlines: The power of scientific discovery harnessed and delivered to your inbox every week. Subscribe to the Michigan Health Lab blog newsletter

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!