Mouse model reveals gut inflammation makes it easier for bacterium to set up shop.

9:39 AM

Author |

The gut-infecting bacterium, Clostridioides difficile, commonly known as C. diff, sickens half a million people and causes up to 30,000 deaths in the United States each year.

Often, C. difficile infection occurs after antibiotic treatment, which inadvertently kills members of the gut microbiota—the community of microbes living in our intestines—that normally bar C. difficile from invading the gut.

However, people with inflammatory bowel disease, also known as IBD, a set of conditions characterized by inflammation of the digestive tract, are at increased risk for C. difficile, even if they haven't taken antibiotics. This suggests that something about the IBD gut supports C. difficile colonization and growth. Yet, the relationship between IBD and C. diff is not well understood.

A recent study from researchers at the University of Michigan Medical School sheds light on factors underlying the development of C. diff in the setting of IBD. Using a mouse model, they show that inflammation and changes in the gut microbiota associated with IBD promote C. difficile intestinal colonization, even without antibiotics.

Down the line, these findings could facilitate the development of strategies to prevent or treat C. diff in IBD patients.

Developing a model to understand the relationship between C. diff and IBD

It's generally believed that IBD occurs when the immune system mistakes normal intestinal microbes for harmful invaders and attacks them, leading to chronic gut inflammation. The cause of C. diff is similarly complex, with the immune system, microbiota, and C. difficile itself playing a role in infection.

When it comes to such complex diseases, scientists use mouse models to experimentally investigate why, and how, they develop. While there are existing models for IBD and C. diff, prior to this study, a system to examine both conditions simultaneously did not exist.

For Vincent B. Young, M.D., Ph.D., professor in the Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases Division at the University of Michigan Medical School and senior author on the study, this technical gap offered a chance to unite phases of a career encompassing work with both C. diff and IBD.

"I started out by exploring the role of the microbiome in IBD using animal models," said Young. Specifically, his early research centered on a mouse model that mimics the dysregulated immune-microbiota interactions characteristic of human IBD. The system uses mice lacking a protein, called IL-10, that normally suppresses inflammatory responses. Without it, animals are prone to developing intestinal inflammation. Whether they do, however, depends on their microbiota.

Most bacteria that live in the mouse gut, including a type called Helicobacter hepaticus, normally co-exist peacefully with their host. However, in animals with altered immune systems, like those lacking IL-10, this bacterium can trigger IBD.

While Young notes that H. hepaticus does not cause IBD in people, the model reflects "principles relevant to human IBD," namely the aberrant interplay between normal members of the microbiota and the immune system in susceptible individuals.

Thanks in part to his involvement with the Human Microbiome Project and experience as an infectious disease physician, Young's research focus eventually shifted away from IBD toward mouse models of C. diff, where it has stayed for the past 15 years.

However, when the study's first author, Lisa Abernathy-Close, Ph.D., a postdoc who was interested in IBD joined the lab, Young thought it would be a perfect time to revisit his earlier work and "see if we could use this model of IBD to understand the intersection between C. diff and IBD."

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

It is well known that C. diff commonly infects people who have had their gut microbiota disturbed by antibiotics, which creates an opening for C. difficile to colonize, proliferate, and damage the intestine. Does IBD do something similar?

"IBD, by the nature of its name, is characterized by gut inflammation. We wanted to figure out if that inflammation in and of itself could predispose animals to C. diff," Young said.

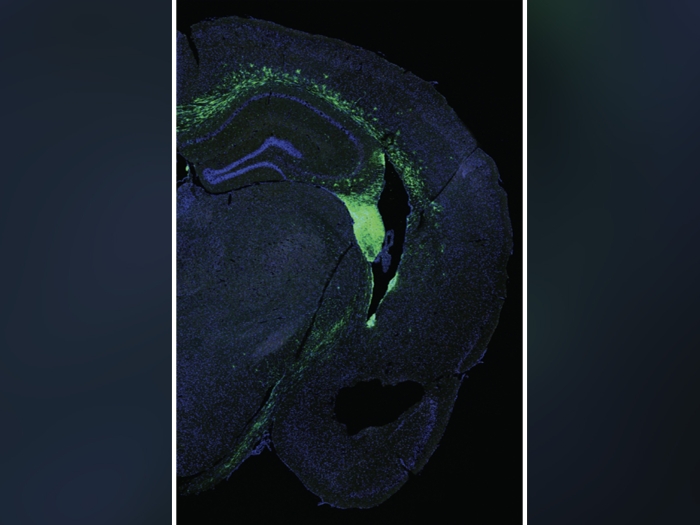

To that end, the researchers colonized IL-10-deficient mice with H. hepaticus to trigger IBD. After two weeks, when the mice had developed significant intestinal inflammation, they were challenged with C. difficile. Said Young, "lo and behold, without antibiotics, animals were colonized by C. difficile," indicating that inflammation alone was enough to promote C. diff.

Notably, the composition of the gut microbiota in mice with IBD, and thus susceptible to C. diff, differed from those without IBD and resistant to infection. This suggests that, like antibiotics, inflammation may alter gut microbiota to create a permissive environment for C. difficile. Additionally, animals with IBD and C. diff had worse disease compared to animals with IBD alone, further mirroring clinical outcomes in human patients, where the onset of C. diff can exacerbate IBD symptoms.

Next steps for investigating C. diff and IBD

The results from this study have multiple implications. For one, having a model to study altered immunity and the microbiota as they relate to IBD-associated C. diff is a technical step forward. This could help develop ways to protect IBD patients from infection.

Additionally, Young notes there are multiple risk factors for C. diff in addition to antibiotics and IBD, including advancing age and having other pre-existing conditions. As such, this system provides "a new way for us to look at what leads to C. diff susceptibility in general, not just for those patients with IBD."

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

"Ultimately," he said, "this could help us understand both IBD and C. diff together, but also separately."

With that, the team is using their model to further disentangle interactions between the immune system, microbiota, and C. difficile colonization and infection. In doing so, they hope to provide a more nuanced understanding of features of the gut that promote or prevent C. diff, in IBD and beyond.

Paper cited: "Intestinal Inflammation and Altered Gut Microbiota Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Render Mice Susceptible to Clostridioides difficile Colonization and Infection," mBio. DOI: 10.1128/mBio.02733-20

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!