Animal model observation may reveal new cause of hypertension.

11:09 AM

Author |

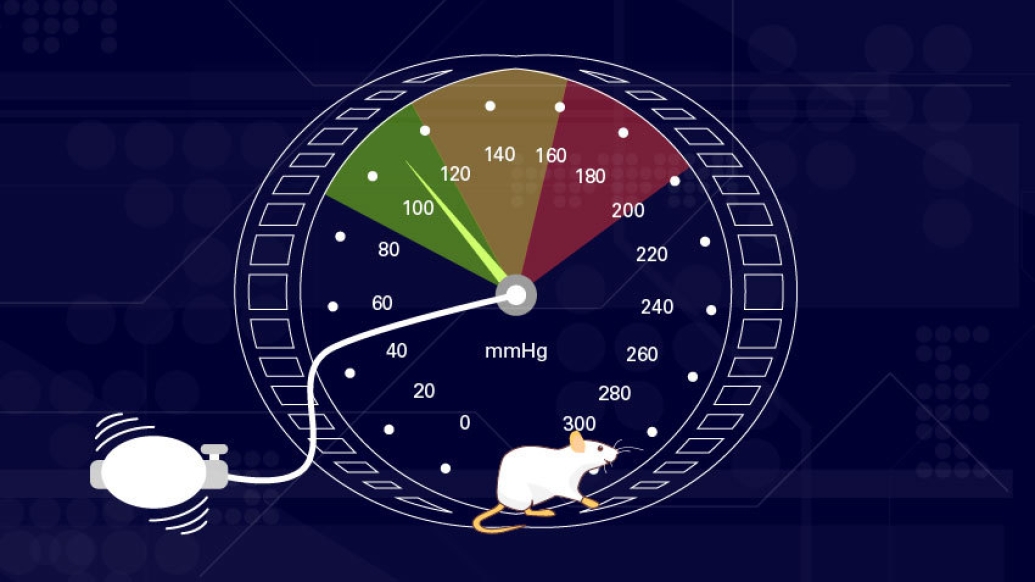

High blood pressure: some people take medication to control it while others commit to low salt diets, exercise or yoga to reduce stress. Blood pressure is a primary vital sign, yet, remarkably, just how the body maintains it is still a mystery.

"We've been studying high blood pressure for 100 years and we still have the same ideas," says Daniel Beard, Ph.D., the Carl J. Wiggers Collegiate Professor of Cardiovascular Physiology. In a new paper in JCI Insight, Beard, Feng Gu, Ph.D., from the department of molecular and integrative physiology, and their team describe a newly observed phenomenon in the way blood pressure is maintained in certain rats.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

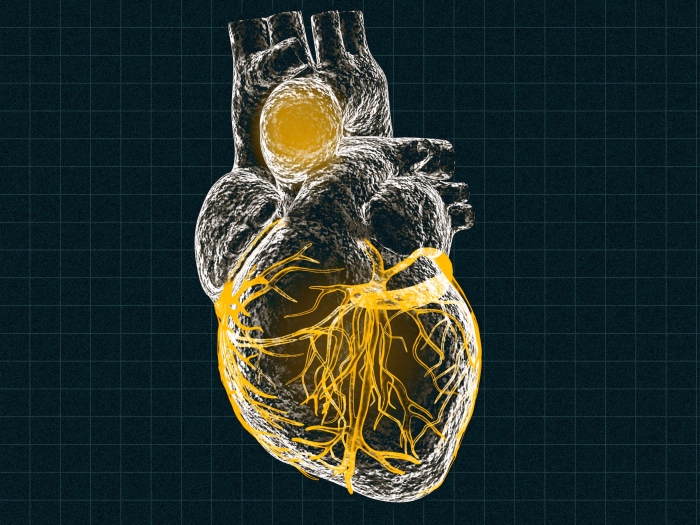

Their discovery comes on the heels of an inquiry into the linkage between stiffened arteries and high blood pressure, known clinically as hypertension. "What happens when you are hypertensive is your arteries get stiffer. But this is thought to be an effect, not a cause," explains Beard. Stiff arteries have a reduced ability to stretch in response to increased pressure. This stretching is controlled by the baroreflex, an automatic neurological response to changes in tension.

"The goal of the reflex is to keep blood pressure steady," says Beard. "If pressure starts dropping, heart rate and cardiac activity go up and if it gets too high, they go down."

The team's hypothesis was that the stiffening in the arteries causes a neural defect, decreasing the ability of the baroreflex to detect arterial stretching and reduce pressure accordingly.

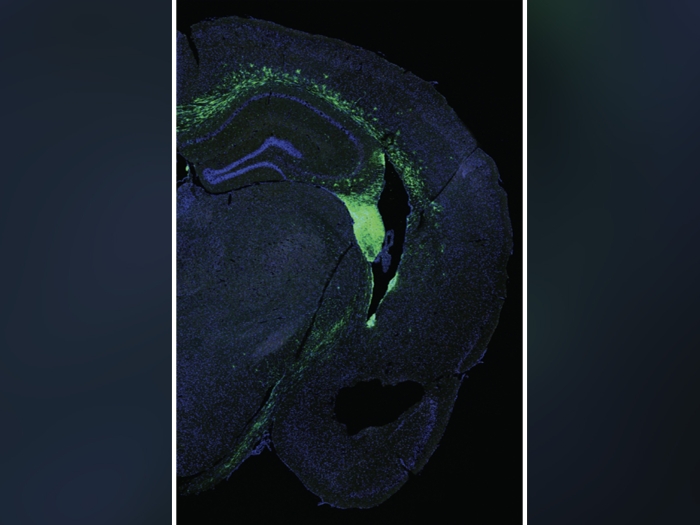

While measuring this effect in rats, they observed that the baroreflex appeared to switch on and off for extended periods of time, up to 5-10 minutes at a time. Spontaneously hypertensive rats—ones who were genetically prone to high blood pressure-- appeared to have more time with the reflex turned off. In fact, Beard's team was able to predict which rats would be hypertensive by the pattern of this baroreflex behavior.

Measuring the dynamic response to blood pressure changes in a human involves tests like a tilt table test, during which a person is strapped to a table that changes positions to measure the cardiovascular response. However, for this study, the team was able to outfit rats with sensors to measure the baroreflex and blood pressure as they went about normal activities. Doing so allowed observation of the on/off phenomenon for the first time.

"First we had to convince ourselves this was real," says Beard. To do so, they compared their animals to rats of a different lineage, ones who developed high blood pressure in response to diet, and saw the same on/off phenomenon. Surprisingly, however, there was no link to blood pressure in these rats. Says Beard, "the baroreflex is contributing to making some animals hypertensive but not others. It may be playing other roles we don't understand."

The team's next goal is to figure out why the baroreflex turns on and off in rats and whether or not the phenomenon exists in people. If so, "it could give us clues about what therapies people may or may not respond to," Beard says.

Paper cited: "Potential role of intermittent functioning of baroreflex in the etiology of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats," JCI Insight. DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.139789

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!