A U-M cancer metabolism expert says scientists are making real headway in understanding the link between dietary sugar and cancer development.

2:00 PM

Author |

What we are learning about sugar may soon have a direct impact on cancer prevention.

SEE ALSO: What Cancer Patients Should Know About Nutrition

Currently, there is no evidence that limiting the intake of sugar (or certain types of sugar) makes any difference if you have cancer, or are trying to prevent cancer through lifestyle choices, according to the National Cancer Institute. But careful controlled studies have not been done. Scientists like those in my lab are excited about current research and the potential for significant discoveries that may relate sugar to cancer development.

Here's what you need to know now about the relationship.

The skinny on sugar

Dietary sugar can come in several varieties, most of which are composed of the simple sugars glucose and fructose. Both of these are found naturally in many foods.

Glucose is the predominant sugar in breads, grains and potatoes; fructose is found primarily in fruits. While they have the same caloric value, the body recognizes and processes them differently. Glucose travels to tissues and muscles, where it is broken down to provide energy. Fructose heads directly to the liver, where it is converted to fat.

Extra sugar, particularly fructose, is often added during food processing. It is these added sugars that have the greatest potential to pile up in someone's diet. That is why nutritionists suggest avoiding sugary breakfast foods, pastries and other sweet foods, as well as sugary beverages, particularly soda, fruit drinks and juices.

The link between fructose and cancer

Among the different types of sugar, glucose and fructose are the two we study in relation to cancer. Between these, fructose is the more nefarious because of the way the body processes it.

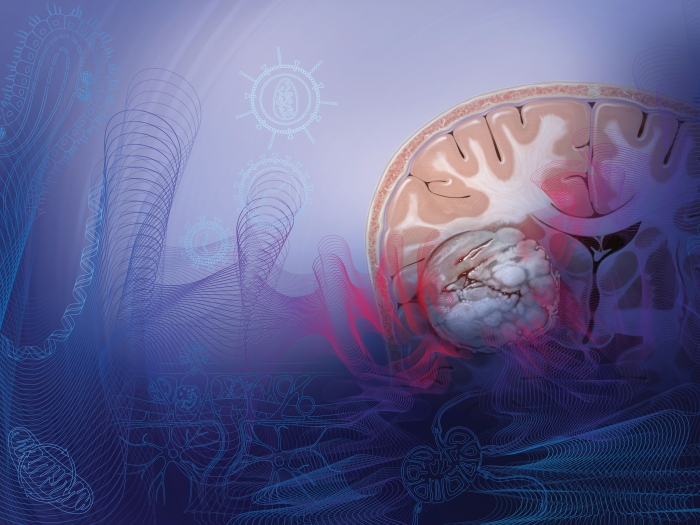

The fat that fructose creates in the liver is released into the blood stream and later stored in the liver and as fat tissue. If not managed, this fat accumulation contributes to insulin resistance, which means the body cannot process insulin like it should, leading to ever-increasing amounts of insulin circulating in the blood stream.

Many types of cancer — including endometrial, breast, ovarian, colorectal, liver, pancreatic and urinary tract cancers — feed on insulin. So, if you have an overabundance of insulin in your bloodstream, the pre-cancer cells can respond to it and grow, and, ultimately, mature into bona fide cancer cells.

People with type 2 diabetes, or who are obese, are particularly vulnerable, because their condition automatically creates more insulin in the bloodstream. Then, eating sugary foods laden with fructose also leads to more fat in the liver and more insulin in the bloodstream.

Anyone looking for ways to eat healthier should limit the amount of fructose in their diet, but those who are obese or have type 2 diabetes should take special care to learn about fructose and how to avoid it.

Tips to cut sugar from your diet

The best defense against sugar, particularly fructose, is to learn how to read and understand nutrition facts on food labels.

SEE ALSO: To Fight Cancer, Put These Foods on Your Plate

Most processed foods — foods that were canned, boxed or otherwise packaged in a factory — contain sugar, which may be labeled as glucose, fructose, high-fructose corn syrup or a host of other names. Even processed foods deemed healthy — such as fruit juices, yogurt with fruit or soups — can pack a sugary punch.

If you are ready to learn more about what is in the processed foods you eat, plan on spending an extra 15 minutes or so at the grocery store for a few weeks. After reading the labels of your favorite foods, you may wind up putting some of those boxes or jars back on the shelf while you look for new, healthier alternatives.

Although we can't say there's a definitive connection between dietary sugar and cancer growth at this time, your body can benefit in all kinds of ways when you eat less sugar. You can get more information on using food as medicine, and recipes and nutrition for cancer patients through the registered dieticians at the U-M Rogel Cancer Center.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!