Often a happy and busy time of year, returning to school can be stressful for some kids. A Michigan Medicine pediatric psychologist offers advice for families.

7:00 AM

Author |

The start of a new school year is filled with excitement for many children.

Others, though, may find that the big event brings stomachaches, tantrums or a reluctance to ride the bus — signs that could indicate the onset of anxiety.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Such worry is understandable. From the prospect of more homework to unfamiliar social situations, there's plenty to trigger feelings of fret.

Those emotions are natural but can become a problem if they interfere with daily life.

Families can take simple, positive steps to prepare for the annual milestone. School, after all, is the foundation for building academic and social skills that lead to a better life. Communication and coping strategies — whether or not a particular fear comes to pass — can help a child succeed in that setting.

Here's how to make the transition easier for everyone.

6 tips for managing back-to-school anxiety

Establish a routine: Before school begins, rehearse your child's daily walking route or determine where to catch the bus. Take advantage of any open houses with teachers and staff if they're offered. And re-establish the family's bedtime and morning routines a week or two in advance so it's not a total change on the first day of school. Practice makes perfect.

Foster trust: For younger kids attending school for the first time, the biggest source of anxiety is separation from parents for a significant portion of the day. Children with experience in day care and preschool often are more well-suited for that transition. The key thing to stress to kids is that you'll come back when school is out. They can only learn that lesson through practice.

SEE ALSO: Parents' Top 10 Children's Health Concerns (and How to Handle Them)

Spot distress signals: When kids are anxious, you see a variety of responses to escape the situation — emotional or behavior outbursts as well as physical symptoms such as abdominal pain and headaches. Parents should acknowledge their child's reaction but encourage the child to stay in the classroom. Most of that goes away in the first couple of weeks.

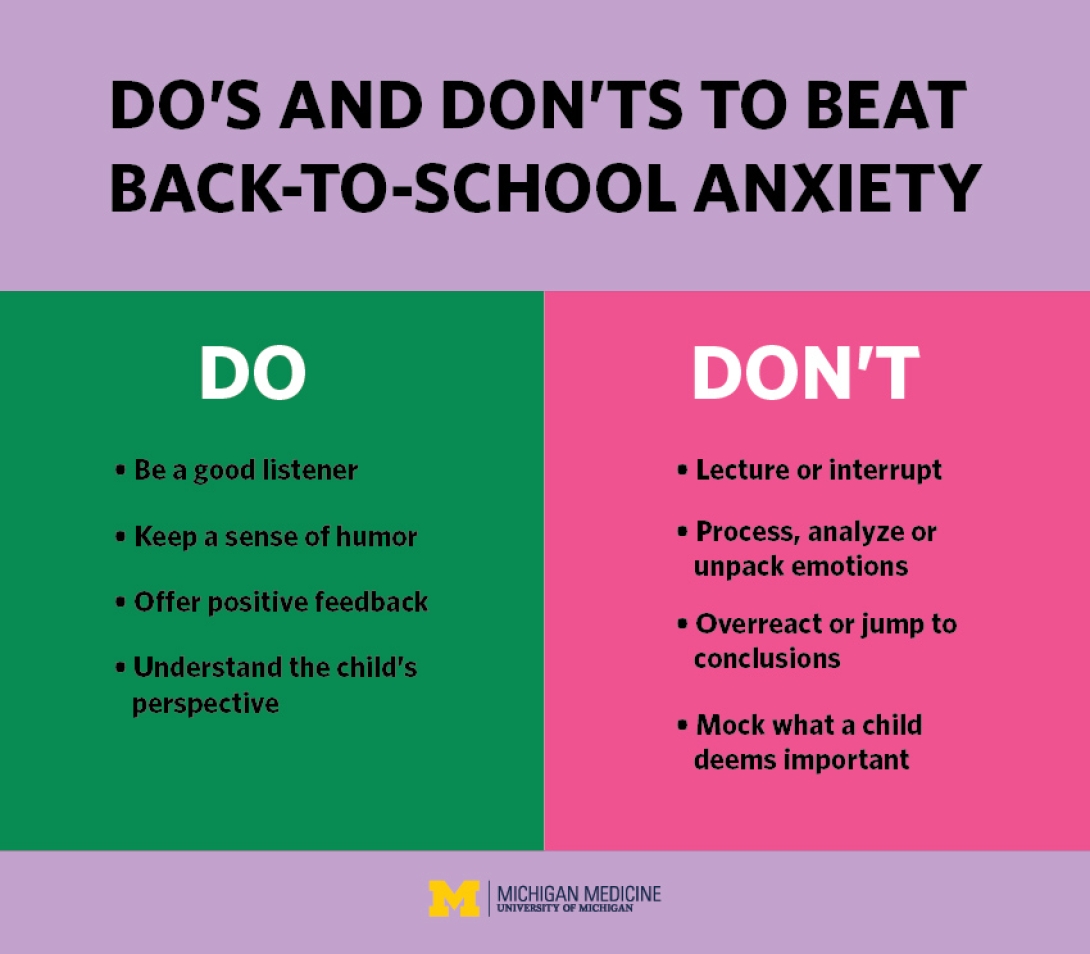

Listen first: Caregivers too often default into leading a discussion. Instead, let children guide the exchange. Do a lot of active listening. Give them reassurance but try not to dismantle or analyze their fears. Rationalization and overprocessing can feed anxiety. Keep the conversation short and at their developmental level. Let them know it will be OK, but don't overdo it.

Acknowledge and defer: Parental attention that accompanies soothing can incite more anxious behavior. That's why I recommend placing reasonable limits by setting aside time each day (but not before bed) when your child can discuss his or her fears. That will help your child learn to self-soothe, stay engaged in life and process these issues at the proper time.

Seek help if necessary: If a child is starting to miss school consistently by more than a few days here or there — or if the physical discomfort doesn't go away after a couple of weeks — talk to your pediatrician or a school guidance counselor. You want to help children learn not to withdraw from the situation at hand. Otherwise, it teaches that anxiety can boss them around.

Explore a variety of health care news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!