The Association of American Medical Colleges recently released its biennial "The State of Women in Academic Medicine" report, a national snapshot of women students, residents, faculty and administrative leaders in academic medicine. It found that although the number of women applying to medical school has increased, women comprise only 38 percent of the full-time academic medicine workforce. Just 21 percent of women are full professors and only 15 percent fill department chair positions. We recently asked some University of Michigan faculty members to comment on the report.

Data like these have motivated scholars like me to investigate whether the pipeline for women in academic medicine is simply slow or whether it is leaky. By investigating the career trajectories of women and men who hold prestigious career development awards from the National Institutes of Health, we have been able to examine what happens to a cohort of men and women with similarly high aptitude, motivation and resources. What we have found is sobering: Women in this group have worse outcomes — in terms of subsequent grant attainment, publications, advancement and salary — than their male peers. Numerous mechanisms have been considered to explain how these differences develop. Perhaps most compelling is the evidence from the social sciences that we all harbor strong unconscious biases that make us more likely to attribute credit to a man than a woman for the same accomplishments.

Reshma Jagsi, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Professor and Deputy Chair in the Department of Radiation Oncology

Research Investigator at the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine

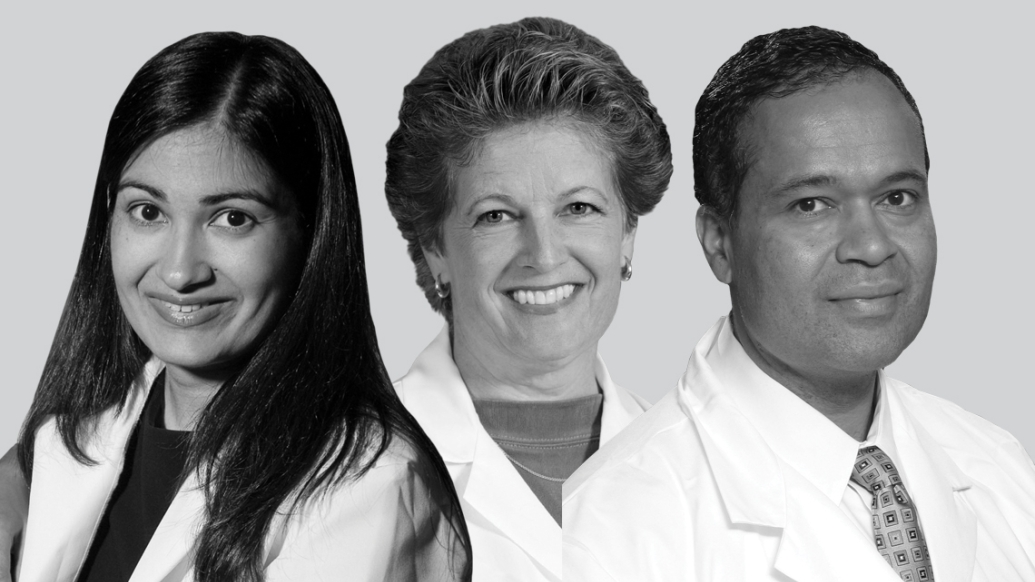

In many specialties women have a profound history of underrepresentation. I was appointed in a field where I was the only woman in the tenure track in the history of the U-M at the time. The assumption then was that women just had no interest in the field. Interestingly, as soon as the number of women began to increase in the field, further increases occurred relatively quickly because there was a critical mass. Suddenly, the field was viewed as an environment where women could thrive. As medical students and trainees develop, it is important for them to see someone who looks like them as successful in a given role. Their perceived options in career paths are thus expanded. Increased diversity results in even greater diversity in the future because the environment is perceived as more inclusive and supportive. Diversity and inclusion will improve even more quickly if we, as a culture, can come to grips with unconscious bias, and how it influences our admission and recruitment processes. There are currently efforts at the Medical School through my office and others to address this important issue directly and honestly.

Margaret R. Gyetko, M.D. (Residency 1985, Fellowship 1988)

Professor of Internal Medicine and Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine

Senior Associate Dean for Faculty and Faculty Development

Some of the issues that are important for advancing women are the climate and the environment they work in, and whether they feel valued and supported. Other factors are mentorship and critical mass. It's hard to be the only woman in your department. So as part of the diversity, equity and inclusion strategic plan on the medical campus, we're going to focus on those three areas and we hope to make improvements in diversity, equity and inclusion for all people including women. The Faculty Development Program recently launched the Rudi Ansbacher Women in Academic Medicine Leadership Program. Now in its second year, the program is extremely successful and gives women the tools to be successful in academic advancement. It's sponsored by the faculty development program here at the UMMS, which is doing a great job and is probably one of the leaders in the country for faculty development and faculty development for women.

David J. Brown, M.D.

Associate Vice President and Associate Dean for Health Equity and Inclusion

Associate Professor in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery