U-M researcher and colleagues study those with extra sharp minds in their 80s and beyond

3:35 PM

After countless well intentioned, but long forgotten, New Year’s resolutions to improve our daily habits, many of us are still looking for the secret to a long, fulfilling life. Keeping our brains healthy and functioning as we age is at the top of the list.

For 98-year-old Elva Gamble, achieving that goal has been, well, a no brainer. A retired registered nurse who worked well into her 80s, Gamble still tools around Detroit in her car and maintains an active social schedule. Her memories of growing up in rural Florida are as vivid as ever.

“My mother lived to age 99 and three months, so I’ve got good genes and longevity in my family,” says Gamble, adding that her healthy diet and nursing know-how have helped her stay mentally sharp and physically active for nearly a century.

At 81, Leonora Koyton is also focused on her mental and physical well being. A former grade school teacher, she worked as a consultant in English and language arts for the Wayne County Regional Educational Service Agency until she was 72. These days Koyton takes daily three mile walks at a mall near her West Bloomfield home and maintains close ties with friends she has known for more than 50 years.

“I’m enjoying life,” she says. “I get up and out every day. I am not sitting at home looking at four walls.”

Robert Burk, 81, a retired aerospace engineer, is an equally enviable octogenarian. He takes care of all the yardwork, gardening, and house maintenance on his two-acre spread in Saline, plays tennis several times a week, and walks daily. Burk has a calculating mind when it comes to financial matters and handles his own taxes and asset management.

“I remember a lot from my childhood, and my daughter has asked me to write down these stories about my life,” he says.

You must remember this

Gamble, Koyton, and Burk come from very different backgrounds, but they do share one important trait that has intrigued University of Michigan neuropsychologist Amanda Maher, Ph.D.

They are all SuperAgers who, in their 80s and 90s, have superior thinking and memory performance comparable to that of middle age adults in their 50s and 60s. And they are all participants in a study based at the University of Chicago, with a site at U-M, called the SuperAging Research Initiative.

“Historically, we’ve thought that our thinking skills and memory are going to get worse as we age,” explains Maher, a clinical assistant professor in Michigan Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry who trained in geriatric neuropsychology at U-M. “SuperAgers are showing us that this cognitive decline is not inevitable ― that not everyone will get memory impairment and develop dementia.

“Instead, we are seeing this remarkable cohort of people over age 80 who are doing extremely well from a cognitive perspective for their age,” she adds. “They are truly remarkable. Their brains move quickly, and they are super sharp. Their memories put mine to shame, for sure.”

Maher and her colleagues at five other sites in the U.S. and Canada are focused on unearthing clues to the unique biological, genetic, and psychosocial factors contributing to SuperAgers’ resilient cognition.

They described the study’s goals and structure in a recent presentation at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on which Maher was senior author. The study is funded by philanthropic support, the National Institute on Aging, and foundations such as the McKnight Brain Research Foundation and the Simons Foundation.

Currently, 30 adults are enrolled in the study at U-M, and Maher’s team is accepting inquiries from others who want to learn more about the study.

“We are studying SuperAgers to find out what is going right with their memory performance, so we can help everybody else enjoy good quality cognitive years later in life,” says Maher, who has devoted her entire 12 year research career to this effort.

A member of the Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, she is interested in understanding what contributes to cognitive health in older age and detect Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders in their earliest stages. The ultimate goal of this work is to apply information gleaned from the investigation of cognitively successful adults to those early in the course of dementia, to slow or prevent cognitive decline.

Looking at brain changes

Are SuperAgers born with good genes that convey long-lasting mental acuity? Or do lifestyle factors such as regular physical exercise, good eating habits, and meaningful social interactions explain their superior memory performance in later years?

From the evidence Maher and other researchers have uncovered thus far, it appears to be a bit of both. The study includes MRI brain scans and blood tests as well as written and computer based cognitive tests.

“It’s a little early in the research to know for sure, but we are seeing evidence of brain biology and physiology, genetics, and some lifestyle factors that contribute to SuperAgers’ above-average cognition,” says Maher.

For starters, MRI imaging reveals that the brain structure of SuperAgers ― and the changes that occur in their brains as they age ― are significantly different from those of cognitively normal 80- and 90-year-olds, she says.

“SuperAgers have a thicker cortex, which is the ‘outer bark’ of the brain,” she explains. “What’s more, their rate of overall brain shrinkage with age is less, often half as much, as their cognitively average peers.”

Research also shows that SuperAgers have a thicker anterior cingulate cortex, which is a part of the brain that plays a role in cognitive processes, such as motivation, decision making, and learning.

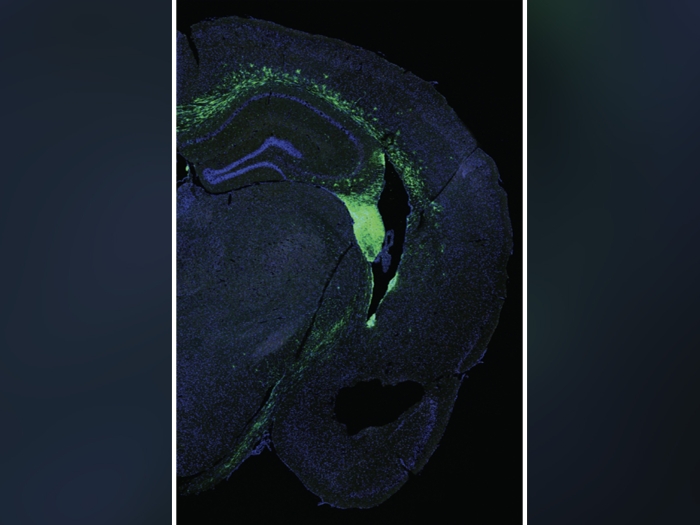

Furthermore, when the brain cells of SuperAgers were viewed with a microscope, researchers found a much greater density of large, specialized neurons (called Von Economo neurons), which are associated with social emotional functioning and social relationships.

Assessing Alzheimer’s risk factors

Using a special Alzheimer’s Disease Polygenic Hazard Score, researchers can distinguish individuals who have certain genetic variants that put them at greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s.

Surprisingly, when SuperAgers and their cognitively average peers are evaluated using this research metric, the scores of the two groups are not significantly different.

“Genetic variables suggest SuperAgers are at the same risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease as elderly participants who serve as controls in our studies,” Maher says. “These findings do not explain why SuperAgers have such good memory performance.”

But comparing the brain cells of the SuperAgers and the control group under a microscope revealed one important difference. SuperAgers had fewer abnormal formations of protein within the nerve cells of their brains. These so called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles are associated with Alzheimer’s pathology.

There was no difference, however, between the two groups in amyloid plaques, which are sticky clumps of material also considered to be a hallmark of Alzheimer’s.

“We’re taking a closer look at these findings in our research,” Maher says.

Maintaining strong social relationships

Compared to cognitively average adults in their 80s and 90s, SuperAgers appear to have warmer, more trusting, higher quality relationships with other people.

“SuperAgers’ social networks are not necessarily larger, but the quality of their relationships seems to be more positive and stronger,” Maher reports. “They also are more physically active and less sedentary during the day.”

Resilience is another characteristic that distinguishes SuperAgers. Participants at other study sites have included a Holocaust survivor and a single mother who struggled to raise her children alone.

“Often, these are individuals who have not had easy lives,” Maher says. “Some have persevered through significant life challenges. That trait is difficult to quantify, however.”

No magic pill

There is no magic pill for slowing or stopping cognitive decline and memory loss as people age. At least, not yet.

But Maher is hopeful her work with the SuperAging Research Initiative will shed light on the factors that enable certain individuals to stay mentally sharp, retain their memories, and pursue active, meaningful lives well into their 80s, 90s ― and even after they hit 100 years of age.

Ultimately, these findings may lead to the effective prevention and treatment of cognitive impairment in older adults.

“SuperAgers are showing us it’s possible to enjoy good cognition as we age,” Maher says. “This is important in a society where we have a negative association with getting older.”

Originally published in Michigan Today.

Written by Claudia Capos

Sign up for Health Lab newsletters today. Get medical tips from top experts and learn about new scientific discoveries every week by subscribing to Health Lab’s two newsletters, Health & Wellness and Research & Innovation.

Sign up for the Health Lab Podcast: Add us on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get you listen to your favorite shows.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!