According to a study, researchers find that disrupted sleep in mice leads to limited to no emotional responses.

9:42 AM

Author |

When you fall asleep, though you may be resting, your brain is wide awake and incessantly working. University of Michigan research suggests that during sleep, groups of neurons activated during prior learning are continuously humming, tattooing and arranging memories into your brain.

U-M researchers have been studying how memories associated with a specific sensory event are formed and stored, using mice as a model. In a study conducted prior to the coronavirus pandemic and recently published in Nature Communications, the researchers examined how a fearful memory formed in relation to a specific visual stimulus.

They found that not only did the neurons activated by the visual stimulus stay more active during subsequent sleep, sleep itself was vital to their ability to connect the fear memory to the sensory event.

Previous research has shown that regions of the brain that are highly active during intensive learning tend to show more activity during subsequent sleep. However, what was unclear was whether this "reactivation" of memories during sleep needs to occur in order to fully store the memory of newly learned material.

"Part of what we wanted to understand was whether there is communication between parts of the brain that are mediating the fear memory and the specific neurons mediating the sensory memory that the fear is being tied to," said Sara Aton, senior author of the study and a professor in the U-M Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. "How do they talk together, and must they do so during sleep? We really wanted to know what was facilitating that process of making a new association, perhaps a particular set of neurons, or a particular stage of sleep. But for the longest time, there was really no way to test this experimentally."

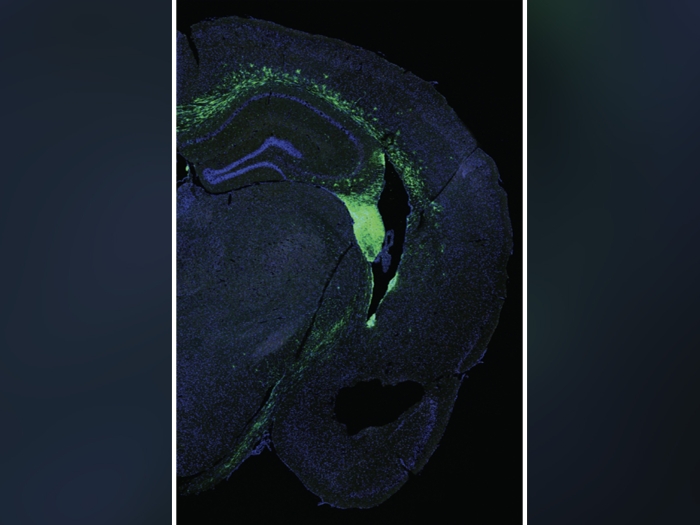

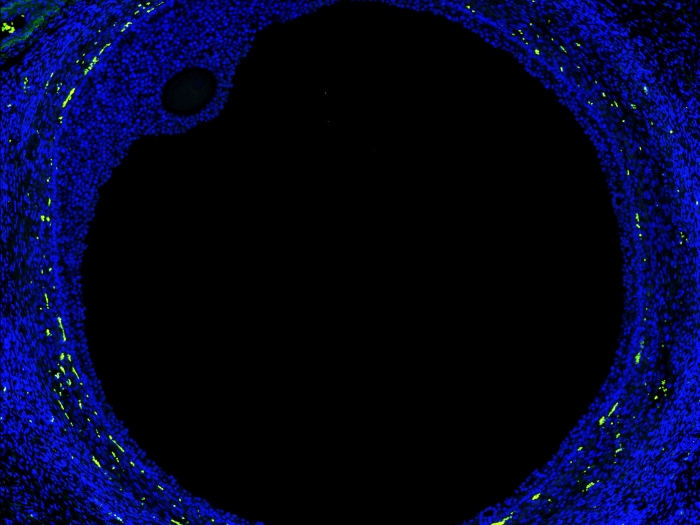

Now, with the advent of tools that can genetically tag cells activated by an experience during a specific window of time, this was not testable. Focusing on a specific set of neurons in the primary visual cortex, Aton and the study's lead author, graduate student Brittany Clawson, created a visual memory test. They showed a group of mice a neutral image, and expressed genes in the visual cortex neurons activated by the image.

To verify that these neurons registered the neutral image, Aton and her team tested whether they could instigate the memory of the image stimulus by selectively activating the neurons without showing them the image. When they activated the neurons and paired that activation with a mild foot shock, they found that their subjects would subsequently be afraid of visual stimuli that looked similar to the image those cells encoded. They found the reverse to be also true: after pairing the visual stimulus with a foot shock, their subjects would subsequently respond with fear to reactivating the neurons.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

"Basically, the precept of the visual stimulus and the precept of this completely artificial activation of the neurons generated the same response," Aton said.

The researchers found that when they disrupted sleep after they showed the subjects an image and had given them a mild foot shock, there was no fear associated with the visual stimulus. On the other hand, those with unmanipulated sleep learned to fear the specific visual stimulus that had been paired with the foot shock.

"We found that these mice actually became afraid of every visual stimulus we showed them," Aton said. "From the time they went to the chamber, where the visual stimuli were presented, they seemed to know there was a reason to feel fear, but they didn't know what they were specifically afraid of."

This likely shows that in order for them to make an accurate fear association with a visual stimulus, they have to have sleep-associated reactivation of the neurons encoding that stimulus in the sensory cortex, according to Aton. This allows a memory specific to that visual cue to be generated. The researchers think that at the same time, that sensory cortical area must communicate with other brain structures to marry the sensory aspect of the memory to the emotional aspect.

Aton says their findings could have implications for how anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, also known as PTSD, are understood.

"To me this is kind of a clue that says, 'If you're linking fear to some very specific event during sleep, sleep disruption may affect this process,'" Aton said. "In the absence of sleep, the brain seems to manage processing the fact that you are afraid, but you may be unable to link that to what specifically you should be afraid of. That specification process may be one that goes awry with PTSD or generalized anxiety."

Paper cited/DOI: "Sex differences in fear memory consolidation via Tac2 signaling in mice," Nature Communications.

This article was additionally reviewed by Allison Mi.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcasts or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

This article was originally posted on the University of Michigan website.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!