Mosquito and tick bites are usually just a nuisance but in some cases, they may also transmit disease. A Mott pediatrician offers parents 6 tips to combat these bugs.

12:36 PM

Author |

They are pesky bloodsuckers that lurk around bonfires, woodsy trails and in the backyard.

And as warmer weather signals sprinkler splashing, s'mores and camp outs for children, it also means the return of these summer spoilers – mosquitoes, ticks and their dreaded bug bites.

While usually just irritating, bites from the two insects may potentially also transmit disease. But choosing the right repellent or protection for children can be confusing for some families, according to the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health at Michigan Medicine.

"There are several different types of repellents, and some are more effective than others. Parents should research the options to choose the best one for their child based on how much time they're spending outside and where," says Heather Burrows, M.D., Ph.D., a pediatrician at Michigan Medicine C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

"Usually mosquito and tick bites are just a nuisance that cause some temporary discomfort. But there's a small and more serious risk that they also spread disease," she adds.

"As long as families take the proper precautions and keep a close eye on kids after spending time outdoors, these insects shouldn't prevent them from enjoying summer fun."

Although uncommon, mosquitos may carry and transmit viruses like Zika, West Nile and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), which can all potentially cause disability or death in humans and animals.

In the summer of 2019, EEE made a comeback in the U.S., with a significantly higher number of cases reported than the typical average of eight cases a year. The virus can cause mild, flu-like illness but a third of those who develop a condition called encephalitis – when the virus inflames the brain – die.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Some summers, ticks have also been more rampant in certain parts of the country, including in Michigan and the Midwest region. One of the diseases they may carry is Lyme disease, a potentially serious bacterial infection that can cause fever, chills, headache and fatigue as well as joint pain and weakness in the limbs.

Burrows offers parents 6 top tips on protecting little ones from these irksome insects.

1. Use DEET, but with caution

Among parents who put bug repellent on their kids, just one in three use sprays containing N,N-Diethyl-meta-Toluamide (DEET), which are most effective against mosquitos, the Mott Poll suggests.

DEET has been tested and approved for use on children ages two months and older when used as directed although experts recommend choosing a repellent with no more than 30% concentration.

Other important recommendations: Only apply once a day, use in an area with good ventilation, don't apply to broken or sunburned skin and don't use it around the mouth, eyes or hands.

"I tell parents to spray a hat, let it dry and then put it on their young child. That will help keep the bugs away from a person's face," Burrows says. "

Because sunscreen needs to be reapplied regularly, Burrows says she doesn't recommend sunscreen-bug spray combinations.

The percentage of DEET determines how long it will last, so Burrows also suggests using the lowest percentage possible.

"If your kids will be outside for only an hour or two, you can get away with a lower concentration — 6 to 7% will last for about two hours," she says. "But if you're going on a long hike in the woods and will be outside longer, you should consider 30% DEET, which may last for six hours."

Families should also wash their hands with soap and water after applying products containing DEET and wash clothes before they're worn again, she says.

2. Consider alternatives for bug protection

About 30% of parents in the Mott Poll use "natural" or homemade products. Oil of lemon eucalyptus may be a good alternative for those who prefer a natural, chemical-free repellent, but should only be used for children over age three.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device or subscribe for daily updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Another option is a product called picaridin. But these alternatives don't last as long as DEET, and will need to be reapplied throughout the day, Burrows says.

Clothing choices can also provide protection, such as making sure children wear pants, long sleeves, light colored clothing and always wear shoes outside.

"When possible, wear long sleeved shirts and pants. Tuck the pants into your socks to prevent ticks from climbing inside the pant leg," Burrows says.

Staying inside before dawn and after dusk also reduces risk of bug bites.

3. Protect against ticks

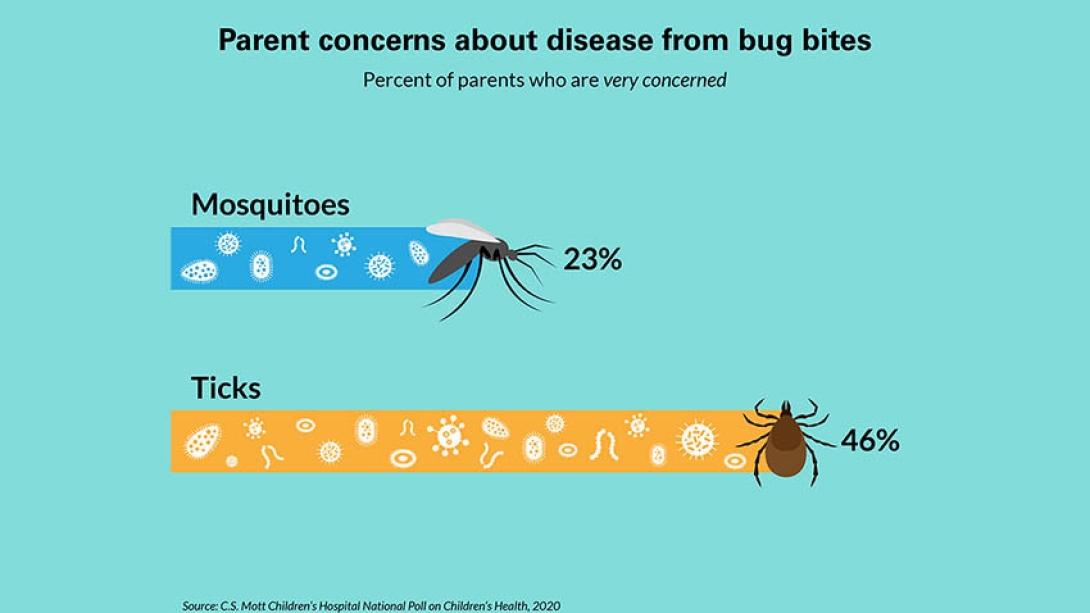

Parents are twice as likely to be concerned about ticks transmitting diseases than they are of mosquitoes, the Mott Poll suggests. But there are two main types of ticks — wood and deer.

Wood ticks are about the size of a watermelon seed. Deer ticks are smaller, somewhere between the size of a poppy seed and an apple seed.

Deer ticks can transmit Lyme disease, but only do so in less than 2% of tick bites. Wood ticks can transmit another infection, Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Parents should be aware that DEET is not very effective against ticks and picardin works better. But the most effective repellent for ticks is to treat clothing with permethrin, which actually kills, versus repels, insects like mosquitoes and ticks. It should never be used on skin.

The application works on clothing for up to six weeks or six washings. It can also be used on sleeping bags and tents. Carefully follow the product's directions for use.

4. Don't forget "tick checks"

Burrows says that when hiking in the woods or high grassy areas, parents should do a "tick check" on everyone in the family as soon as they come inside. Thoroughly check in and around the ears, inside belly buttons, behind knees, between legs, in armpits and in hair.

Although ticks will burrow into the skin in order to suck on a person's blood, their bite is painless.

"Because you won't feel them bite, you'll need to look for them carefully," Burrows says.

"An infected tick usually has to stay attached for 24 hours before there is any chance of transmitting the organism that causes Lyme disease, so finding one right away is important."

5. Remove ticks properly

Should you discover a tick, don't panic – but don't wait to remove it, either – Burrows says.

If you find a wood tick, use tweezers to remove it. Grasp the tick close to where it's attached to your skin and pull straight up without twisting or crushing the tick. When dealing with the smaller deer ticks, if you don't have tweezers, you can scrape them off with a fingernail or the edge of a credit card.

In either scenario, wash the bite area and your hands with soap and water after removing a tick. Then apply an over-the-counter antibiotic ointment to the bite site.

"If you're worried about potential tick-transmitted diseases, place the tick in a plastic bag after removal so you can take it to your doctor if any symptoms develop," Burrows says.

6. Know the signs to seek medical care.

Nearly half of parents polled give their children oral antihistamines to provide relief from bites while 40% prefer calamine lotion and 27% use rubbing alcohol. Many parents also use home remedies, including an ice cold rag, oatmeal baths and baking soda.

But if a child develops fever, a headache, body aches and a rash within 3-14 days of a bite, parents should contact their child's health care provider, Burrows says.

A bull's-eye-shaped or circular rash around the bite site can also be an indication of Lyme disease. If Lyme disease has been transmitted, the rash will typically appear within three to 30 days.

Other tickborne illnesses have their own rash patterns. Rocky Mountain spotted fever looks just like it sounds — a spotty rash in the affected area.

"If children have any of these symptoms, they should see their doctor immediately for treatment," Burrows says.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!