Computer modeling links a person's genes to whether producing more antibodies will help them fight off the disease.

10:39 AM

Author |

Genetics play an important role in how our bodies respond to vaccines and booster shots, suggesting that certain protective responses elicited by vaccination could be more effective with personalization, according to a new study led by University of Michigan researchers.

The team also identified a particular form of an antibody-related gene that predicts, at a population level, whether boosting to produce more antibodies will be effective for increasing innate immune responses.

"What's most interesting with this work is the concept of personalized variability and understanding direct links between vaccine responses and different genes people have," said Kelly Arnold, U-M assistant professor of biomedical engineering and senior author of the paper in Frontiers in Immunology.

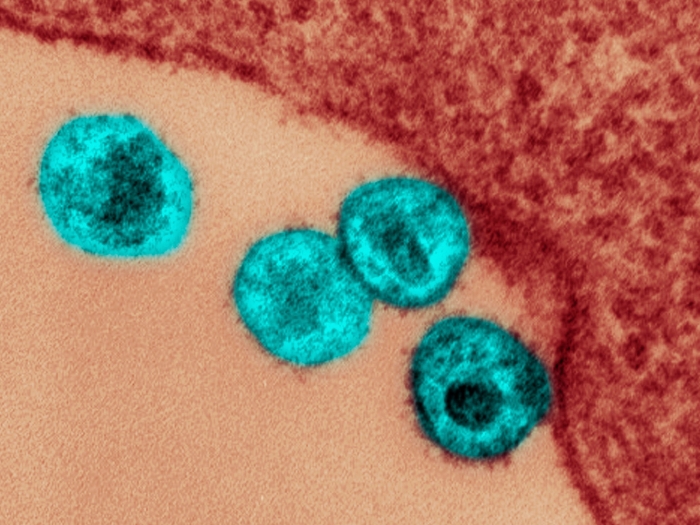

The study explored how people may respond differently to conventional boosting, which reexposes the immune system to the virus (or some portion of it) to increase antibody concentration.

However, in some people, the increase in antibody concentration may not matter as much because their genes encode for immune receptors that aren't as good at sticking to the antibodies—they're said to have a lower affinity.

As a result, a person can have a respectable antibody count and still have a poor immune response. So one theoretical alternate immune-boosting route could be to design vaccines that tweak the structure of the antibodies—making those antibodies more likely to stick to a person's immune cell receptors.

"Depending on your genetic background, we've found that vaccine boosting may be more or less effective in activating certain innate immune functions," Arnold said. "And in some people, where boosting the concentrations of antibodies was ineffective, being able to change the affinity of antibodies could be the more successful route. Though this is still a theoretical concept and not yet possible in practice."

Arnold's team, working with partners in Australia, Thailand and the U.S., created a computer model to determine how different genetic factors influence innate immune responses induced by vaccine boosting. It uses data and plasma samples obtained by the University of Melbourne from the only moderately protective HIV vaccine trial to date.

The plasma samples from trial participants—basically blood samples minus the red blood cells—showed the amount and type of antibodies produced after vaccination.

"In a mixed population of people, we've also shown how one specific genotype would drive whether that population was responsive to changes in antibody concentrations expected from traditional boosting," Arnold said.

Modeling showed that, in a gene that encodes for a specific type of antibody (IgG1), different variations can predict how effective boosting to increase antibody levels will be in a given population. Some populations in the HIV trial showed that increasing antibody levels resulted in no change in the innate immune functions that were being evaluated.

"What that tells us is that in populations with certain genetic variations, traditional boosting methods to increase antibody concentrations may not be as effective at improving innate immune functions," Arnold said.

Adjuvants are the vaccine ingredients designed to improve the body's immune response.

Last year, Arnold's team utilized data from the same trial to highlight why certain vaccines influence people differently. In the future, both studies could lead to new design principles for vaccines that take an individual's personalized characteristics into account.

The research was funded by the Australia National Health & Medical Research Center, the American Foundation for AISD Research Mathilde Krim Fellowship and the University of Michigan.

The collaboration included the University of Melbourne, Monash University and the Burnet Institute in Australia; Mahidol University, the Ministry of Public Health and the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Science in Thailand; and the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States.

This article was originally published by Engineering Research News.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!