Thousands of samples from patients with coronavirus infections, stored at -112F, hold potential to unlock important secrets

12:23 PM

Author |

The forecast outside calls for temperatures below freezing, and wind chills below zero, for much of the next two weeks in Michigan.

But that's a heat wave compared with what's happening inside a row of freezers at the University of Michigan.

The forecast for them? A very consistent -112 degrees Fahrenheit, or -80 degrees Celsius.

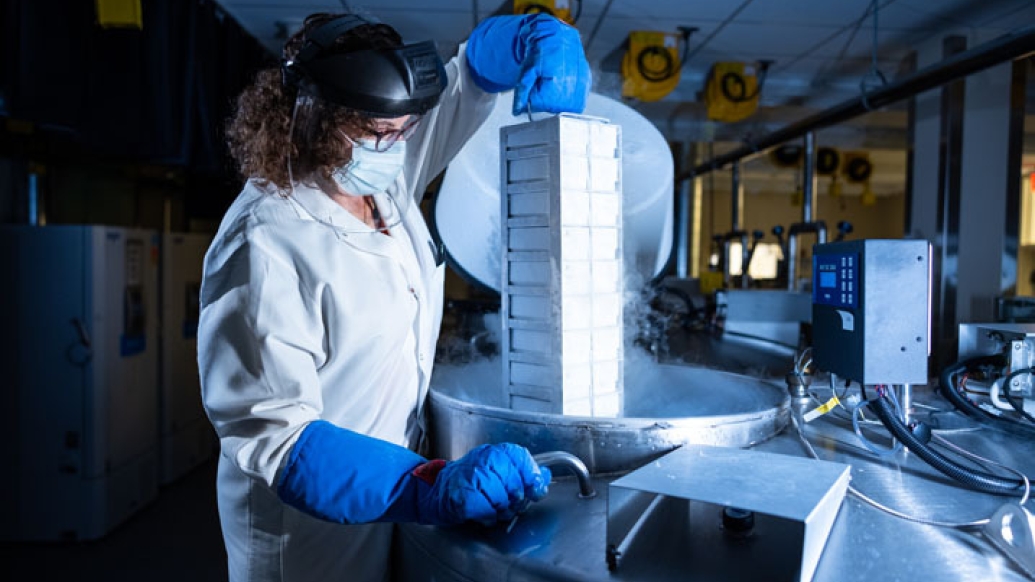

That's just fine with U-M scientists, though. Because inside those freezers sit tens of thousands of tiny vials filled with blood plasma, DNA and nose swabbings from people with COVID-19.

Whether they were hospitalized at Michigan Medicine, U-M's academic medical center, or volunteered to have blood drawn or their nose swabbed by a U-M team after they recovered at home, those patients have helped create a vast frozen COVID-19 library.

It's called the COVID-19 Biorepository. And ever since it launched in spring of 2020, it's been a trove of discovery for U-M researchers. As of this week, the COVID-19 Biorepository includes 23,365 samples from more than 2,100 people.

The ultra-cold temperatures help keep the samples intact, preserving the fragile genetic material, proteins, immune-response molecules and cellular signals that can reveal how the virus wreaks havoc in the body.

Like Podcasts? Add the Michigan Medicine News Break on iTunes, Google Podcast or anywhere you listen to podcasts.

"The faster we can get samples from a patient or research volunteer into our freezers, the more we can preserve the potential to unlock new discoveries," says Victoria Blanc, Ph.D., who directs the Central Biorepository run by the U-M Medical School's Office of Research that includes the freezers devoted to COVID-19 samples. "Sometimes it's a matter of hours, and every minute matters."

SEE ALSO: COVID-19 Variants: What Do New Mutations to SARS-CoV-2 Mean?

Blanc's team meticulously logs and tracks every sample via barcodes, and makes careful decisions about how they can be used.

First findings already published using the U-M COVID-19 Biorepository

Already, U-M scientists have taken tiny samples called aliquots from many of those frozen vials, thawed them carefully in their laboratories, and used them to study the coronavirus and the effects it has.

They've even published some of their first discoveries based on what they found in those samples, sharing their insights with the world as the battle against the pandemic continues. That new knowledge could help shape treatment and prevention.

The faster we can get samples from a patient or research volunteer into our freezers, the more we can preserve the potential to unlock new discoveries.

"The Biorepository team has been hugely instrumental in connecting us with other researchers, leading to collaborations that are not only related to better utilization of limited resources, but a consolidation of expertise leading to higher-impact studies," says Matthew Cusick, Ph.D., a researcher in the U-M Department of Pathology who studies immune system responses. "Simply put, the Biorepository team has been amazing at connecting the U-M scientific and medical community."

The discoveries made so far include important findings about the blood clots that often occur in COVID-19 patients and contribute to the deaths and long-term effects it causes.

SEE ALSO: Keeping Our Patients Safe During COVID-19

Another U-M team using the samples has found that some people with COVID-19 actually face the opposite: a serious risk of uncontrollable bleeding, which could be made worse by efforts to prevent clots with medication.

Still another team is studying the genetics of the SARS-CoV2 coronavirus itself, including the new variants that have been identified in people in Ann Arbor and other areas.

"The COVID-19 Biorepository has been absolutely instrumental to our work throughout the pandemic," says Adam Lauring, M.D., Ph.D., a virologist and infectious disease physician who leads a U-M team studying the virus's genetic makeup and changes. "They've helped us store, aliquot, and distribute residual samples from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. By collaborating with the Biorepository team, we've been able to sequence over 1,500 viruses from our community. This has helped us define how COVID-19 spreads."

A growing collection of COVID-19 samples

Many of the samples in the freezers were collected through a special effort led by the Michigan Clinical Research Unit, which provides support for Michigan Medicine studies involving patients and community members. Hundreds of people who had recently recovered from COVID-19 came to the research unit clinic to donate their samples.

The COVID-19 Biorepository was started under the leadership of U-M Medical School assistant dean for clinical research Anna Lok, M.D.

"Early on in the pandemic, we heard from multiple researchers who hoped to access COVID-19 patient samples from our hospitals, so they could launch research to address many important questions," says Lok. "We decided to coordinate the requests and process, and most important not overburden an already hard-hit patient population and the teams that care for them. The result has helped researchers who are studying everything from why some patients develop severe disease and others don't, to the body's immune response, to markers along the path of severe disease that could be potential targets for new treatments."

The freezers also hold samples from frontline U-M employees collected through the Immunity Associated with SARS-CoV-2 study based at the U-M School of Public Health and led by Aubree Gordon, Ph.D. That study is still recruiting participants to study risk of exposure, and help explore how long immunity to the virus lasts among people who have previously been infected.

SEE ALSO: COVID-19 Through the Lens of Basic Science

Located at the North Campus Research Complex, the Central Biorepository was founded several years before COVID-19 arrived. It includes more than 550,000 frozen samples from more than 111,000 people – those with a wide array of conditions, and healthy volunteers from various studies.

Terrence Wong, M.D., Ph.D., leads a research group that studies how mutant hematopoietic cells – the kind of stem cells that give rise to blood cells – influence overall human health.

"The COVID-19 Biorepository samples are allowing us to determine if these cells impact COVID-19 morbidity and mortality," he explains. "More broadly, the Biorepository is giving us a head start in the development of future studies to assess the impact of these cells on human health in general."

Several freezers at the Biorepository house samples from participants in the Michigan Genomics Initiative, part of U-M Precision Health. That registry of people who have had surgery at Michigan Medicine in the past few years, and agreed to allow researchers to study their samples and contact them for surveys, has also proven useful in COVID-19 research.

MORE FROM THE LAB: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Blanc notes that laboratory-based research sometimes takes years to pay off – so many more discoveries may lie ahead.

The vaccines and treatments that have been developed in the past year for COVID-19 relied in part on decades of past research – studies on coronaviruses in general, on the immune system's intricate workings, and on messenger RNA, the kind of short-lived genetic material that now forms the basis for the first two COVID-19 vaccines approved in the U.S.

So when you're cursing the cold weather, just remember that cold can be our ally in the fight against COVID-19.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!