Medical student shares journey with painful disease disproportionately affecting African Americans and why she wants to help others.

10:17 AM

Author |

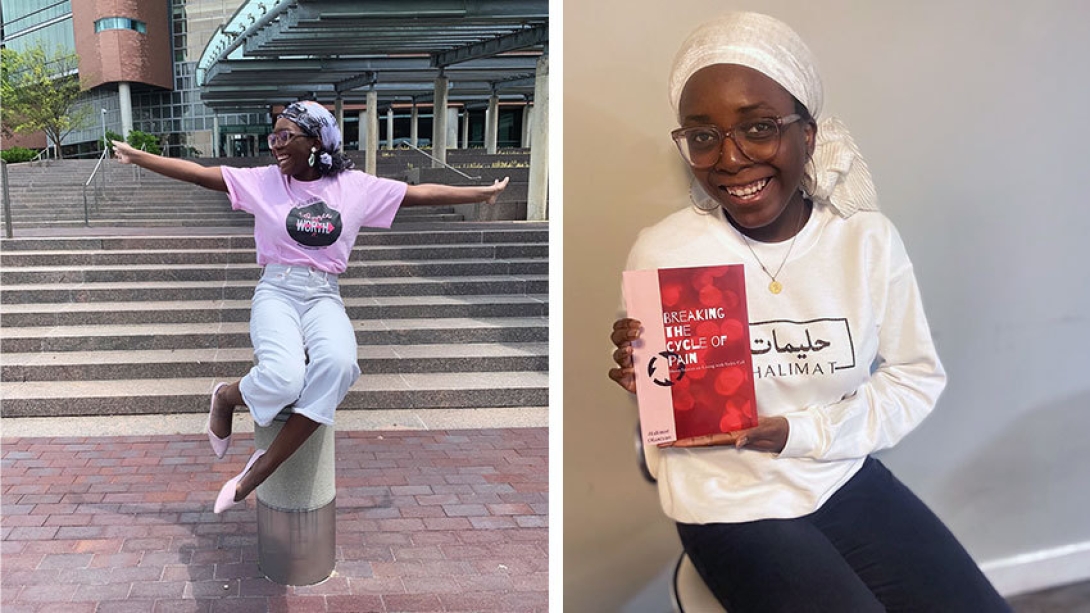

Halimat Olaniyan was about seven years old when she experienced such excruciating pain that she left elementary school and ended up in an emergency room.

There, a series of tests revealed a diagnosis that had been missed at birth in her native country Nigeria: sickle cell disease.

At the time, Olaniyan didn't completely understand what that meant, only that it was the reason she'd have uncomfortable bouts of sickness that would keep her out of school for up to weeks at a time. But years later, as a University of Michigan student receiving care at U-M Health C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, she grew more engaged with her health journey.

And today, the 25-year-old is attending medical school and helping others as a sickle cell disease advocate.

"I used to think I was the only one who had this disease," said Olaniyan, who is set to graduate from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in 2023. "At Michigan I felt like I was an active part of my care. I found a whole new support system.

"I am privileged enough to have access to resources that help me manage my disease but that's not the case for everyone. I hope to do work that helps other sickle cell patients with the support they need to be successful."

An inherited condition disproportionately affecting African Americans

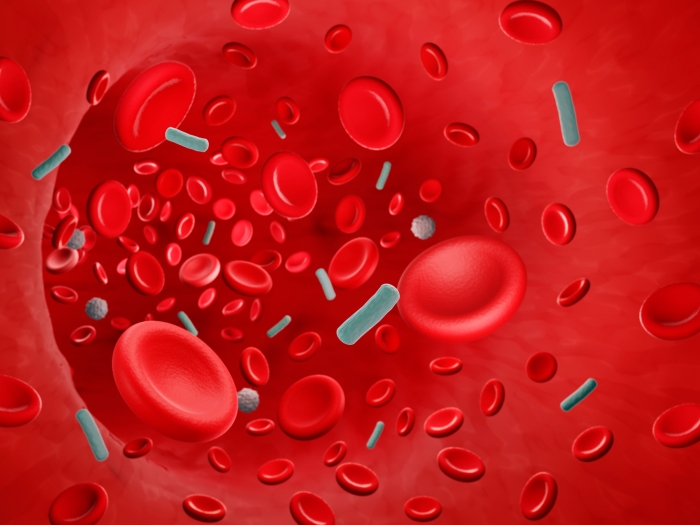

Sickle cell disease is an inherited group of blood disorders that affect hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. It affects millions of people throughout the world but impacts African Americans at disproportionate rates. In the United States all newborns are screened for the condition.

Red blood cells are usually round and flexible so they move easily through blood vessels. But in sickle cell, some red blood cells are shaped like sickles that can become rigid and sticky, preventing them from properly delivering oxygen to all parts of the body.

These crescent shaped cells die early, which causes a constant shortage of red blood cells. They can also get stuck and clog the blood flow, which may not only cause pain but other serious problems such as infection and stroke.

While there's no cure for most people, treatments can relieve pain and help prevent complications associated with the disease.

"Many families are just devastated by this diagnosis," said Sharon Singh, M.D., a pediatric hematologist and oncologist at Mott who oversaw Olaniyan's care at U-M. "This is an unpredictable and chronic disease requiring complex specialized care and the patient journey can be very challenging. It's important to have a team supporting you along the way to help you make the most informed decisions and address all aspects of your care.

"It's so wonderful to see a patient pursue her dreams and find success like Halimat has. Not only is she thriving and coming full circle by going into the medical field herself but she's advocating and educating others, which is incredible. She brings hope."

Singh, who recently traveled to Washington D.C. for the U.S. Senate's introduction of a sickle cell expansion bill to enhance medical training, says while patients with sickle cell are living longer and healthier lives, there's still a great need for more investments in research.

U-M researchers have joined colleagues across the country in efforts to better understand the complications of sickle cell disease and find new treatments for patients through several research studies.

"This is a disease that predominately affects people from the most low-resourced and disadvantaged communities," Singh said. "It's also not always easy to get treatment depending on where you live. We have a shortage of providers who care for adult sickle cell patients, which can cause disruptions in care for patients aging out of pediatric care."

"Hopefully as we make the disease more visible, we can fill gaps in funding and resources."

Empowered and "unstoppable"

Olaniyan says she's lucky to mostly experience mild disease, with painful episodes much less frequent now. Occasionally she has fatigue, anemia and joint pain, often triggered by stress and a sign from her body that she needs to take a break.

With Singh's support, she also began managing the disease with hydroxyurea, a drug therapy that reduces painful episodes and long-term harm and complications.

She says the multidisciplinary approach to care at Mott was critical for her, recently even interviewing Singh for sicklecell.com about this strategy to treatment. In addition to seeing Singh at the Mott clinic, Olaniyan had access to a pain specialist, registered nurse, social worker, psychologist, dietician and an obstetrician gynecologist who specialized in sickle cell.

"Having specialists dedicated to addressing all of these unique parts of my health affected by sickle cell disease made such a big difference," she said. "I was able to work through some of my anxiety and other ways this condition has affected me and get educated in a safe and open way.

"Sickle cell does a really good job of making people feel powerless. I felt like I had an abundance of people and places to look to for help. I felt like I had some power back."

Olaniyan's care team even introduced her to North Star Reach where she spent time as a camp counselor for groups of kids with sickle cell disease. She's also been engaged with advocacy work by writing for various sickle cell support groups and platforms and publishing a book about her experience and motivation to pursue medicine.

At medical school, Olaniyan sits on patient panels as well and gives regular talks on sickle cell to other medical students, providers and nurses. She plans to apply for residency in pathology and eventually focus on hematology and transfusion medicine for sickle cell patients.

"I would tell others with this diagnosis to always keep an open dialogue about the disease and how it's affecting them. It's still hard for me to tell people I don't feel good sometimes but hiding the pain adds to the stigma," she said.

"It's also important not to limit yourself and that the people supporting you don't limit you either. My mom always told me I could do whatever I wanted to do even when I would hear people say I might not live past 30. She was unwavering in her support and made me feel unstoppable. I was led to believe it was possible to find a way to be successful in whatever I chose to do. Don't let any barriers stop you."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!